Designing Data Intensive Applications Notes: Ch.9 Consistency and Consensus

Mohamed Kassem | November 04, 2023

Continuing our series for “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” book.

In this article, we will walkthrough the second chapter of this book Chapter.9 Consistency and Consensus.

Table Of Content (TOC)

- Consistency Guarantees

-

- Linearizability VS Serializability

- When need to rely on Linearizability?

- The CAP theorem

- Linearizability and Performance

- Implementing Linearizable Systems

- Ordering Guarantees

- Sequence Number Ordering

- Distributed Transactions and Consensus

- Atomic Commit and Two-Phase Commit (2PC)

- Distributed Transactions in Practice

- Membership and Coordination Services

The simplest way of handling system faults is to simply let the entire system fail, and then show an error message. But, the best way is to have a general-purpose abstraction with useful guarantees that we can implement.

One of the most important abstractions for distributed systems is consensus: that is, getting all of the nodes to agree on something (Like in single leader replication , when leader is dies and we need to fail over another node to be come the leader, the implementation of this consensus can prevent problems like if two nodes believe that they are the leader: split brain problem).

Consistency Guarantees

Most replicated databases provide at least eventual consistency, with such a weak guarantee we need to be aware of its limitations, and not to assume too much, as these limitations only appear when there is a fault in the system.

Systems with stronger guarantees may have worse performance or be less fault-tolerant than systems with weaker guarantees. Nevertheless, stronger guarantees can be appealing because they are easier to use correctly.

There is some similarity between consistency models and transaction isolation levels. Isolation levels is primarily about avoiding race conditions due to concurrently executing transactions (Isolation guarantee), whereas distributed consistency is mostly about coordinating the state of replicas in the face of delays and faults (ordering/recency guarantee).

Linearizability

Linearizability achieve strong consistency that guarantee that every client would have the same copy/view of the data and all operations on it are atomic, and you wouldn’t have to worry about replication lag.

linearizability (also known atomic consistency, strong consistency, immediate consistency) is recency guarantee..

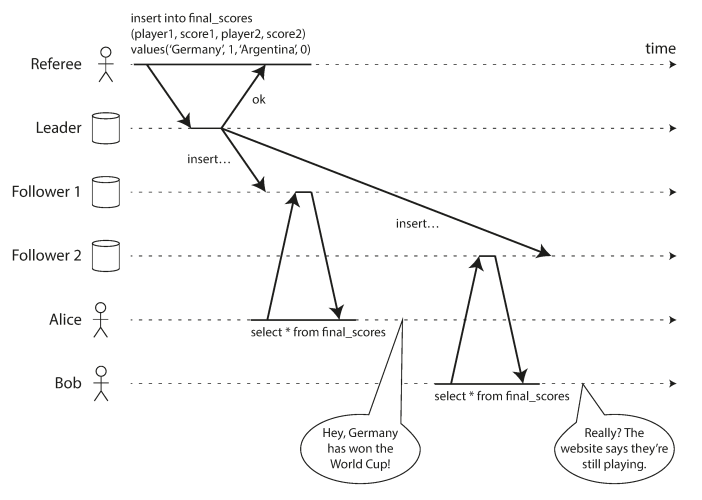

The following examples shows an system is not linearizable, causing football fans to be confused.

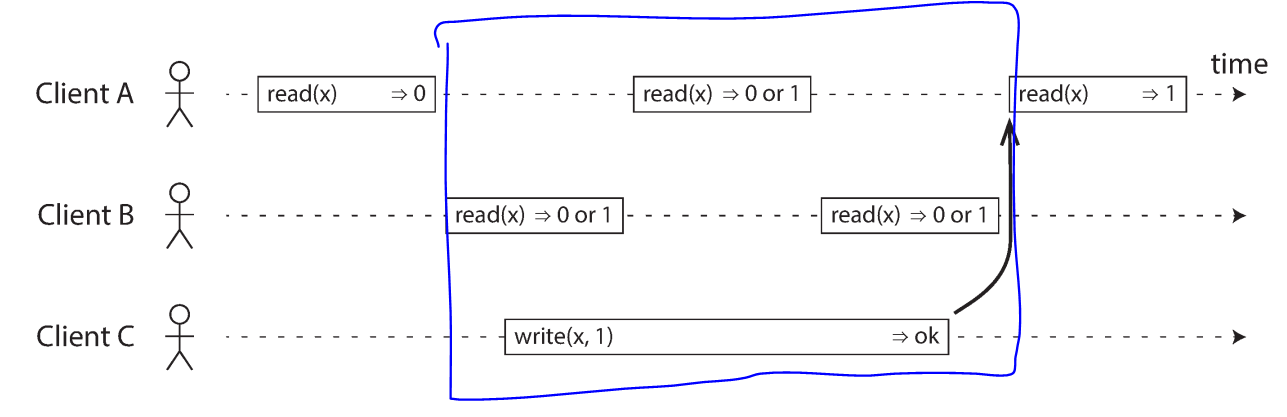

To understand concurrent operations (reads and writes), see the following example what shows uncertainty, it may return either the old or the new value.

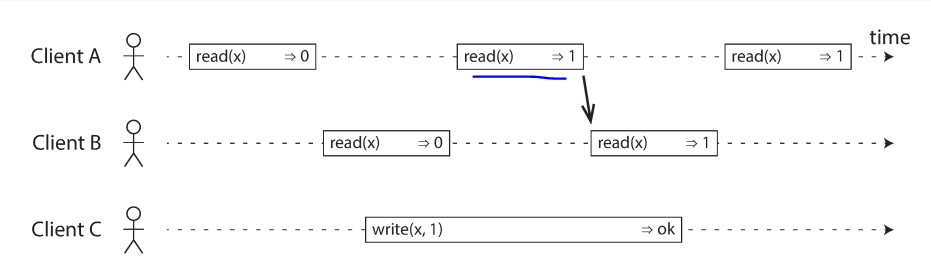

To achieve linearizable: you consider that once a new value has been written or read by any client, all subsequent reads must also return the new value. Even if the write operation has not yet completed.

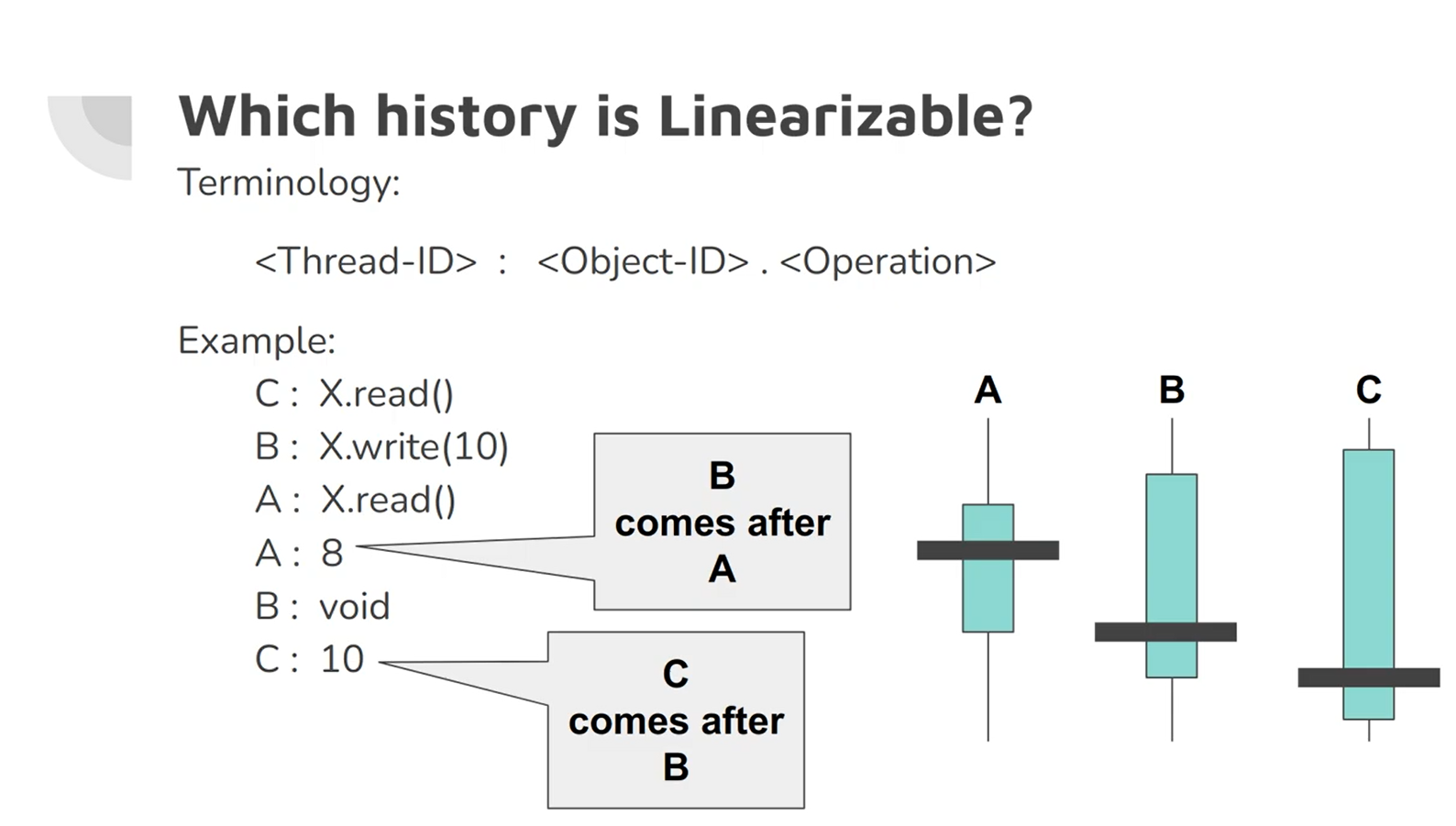

In a linearizable system we imagine that there must be some point in time (between the start and end of the write operation). the following screen shows an example of three concurrent threads at some point in the time span has the actual read/write the value.

The following example shows the timing diagram to visualize each operation taking effect atomically at some point in time.

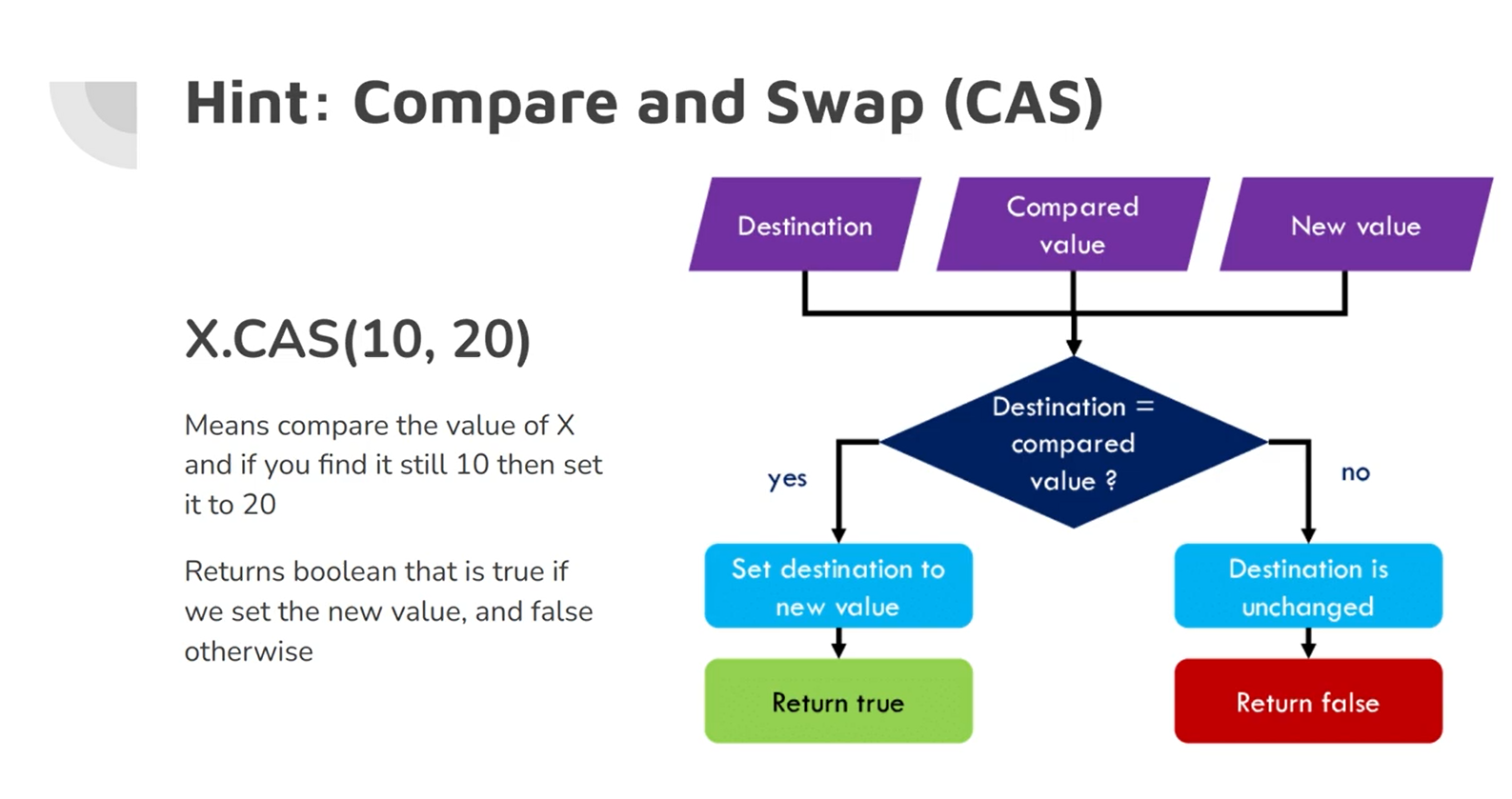

cas(x, Vold, Vnew): is hardware/process atomic operation. Like read and write operations

If the current value of the register x equals Vold, it should be atomically set to Vnew. If x ≠ Vold then the operation should leave the register unchanged and return an error. r is the database’s response (ok or error)

It’s possible to test whether a system is linearizable by recording the timings of all requests and responses and check whether they are sequential.

Linearizability VS Serializability

- Serializability is an isolation guarantee property of transactions, where every transaction may read and write multiple objects concurrent. Executed in some serial order.

- Linearizability is a recency guarantee on reads and writes of a register.

A database may provide both serializability and linearizability, and this combination is known as strict serializability.

Implementations of serializability based on two-phase locking or actual serial execution are typically linearizable. While serializable snapshot isolation is not linearizable.

When need to rely on Linearizability?

- Locking and leader election: Make sure that only one leader is elected by using a lock. To make system linearizability, ZooKeeper used to implement distributed locks and leader election by using consensus algorithms.

-

Constraints and uniqueness guarantees: Uniqueness constraints in database (such as username or email, if two people try to concurrently create a user or a file with the same name, one of them will be returned an error) should be linearizability. To implement it add lock on their chosen username or by compare-and-set CAS(username, empty, newUserName).

- Another examples that make sure that a bank account balance never goes negative, or that you don’t sell more items than you have in stock in the warehouse, or that two people don’t concurrently book the same seat on a flight or in a theater.

-

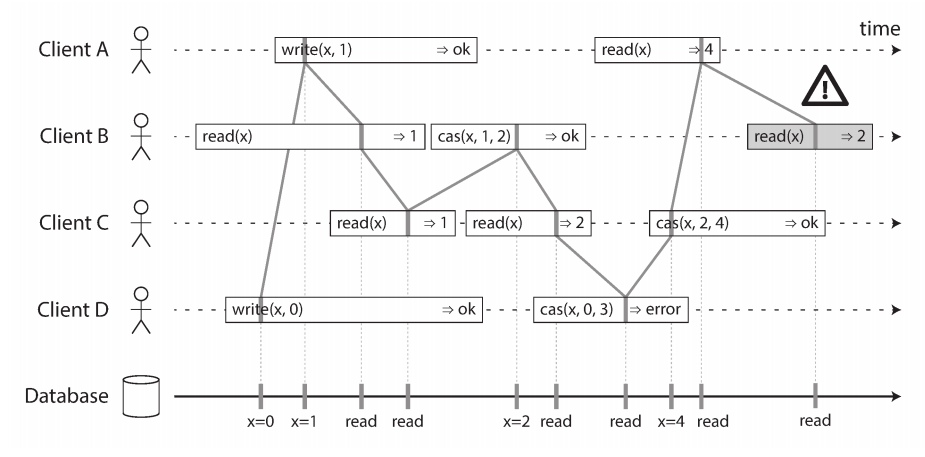

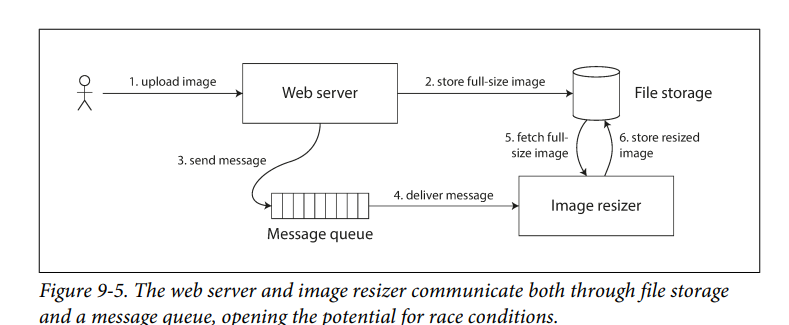

Cross-channel timing dependencies: if the system uses two different communication channels depending on each other. The system should be Linearizability to prevent race conditions.

- For the following examples shows two different communication channels (web server and image resizer) If the file storage service is linearizable, then this system should work fine. If it is not linearizable, there is the risk of a race condition: the message queue (steps 3 and 4) might be faster than the internal replication inside the storage service. In this case, when the resizer fetches the image (step 5), it might see an old version of the image, or nothing at all.

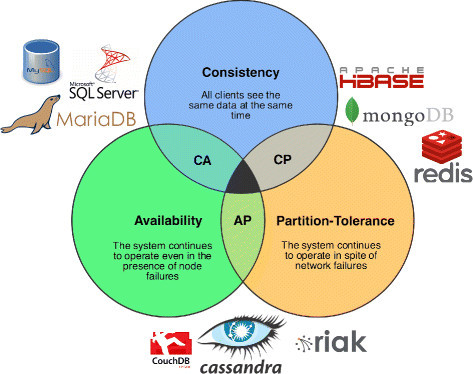

The CAP theorem

https://www.ibm.com/topics/cap-theorem

This CAP theorem show that you cannot achieve the 3 principles together into the distributed systems. You can achieve only two of them.

- CA ⇒ has strong/strict consistency

- AP ⇒ has eventual consistency

- CA ⇒ If your application requires linearizability, and some replicas are disconnected from the other replicas due to a network problem, then some replicas cannot process requests while they are disconnected: they must either wait until the net‐ work problem is fixed.

- AP ⇒ If your application does not require linearizability, then it can be written in a way that each replica can process requests independently, even if it is disconnected from other replicas (e.g., multi-leader). In this case, the application can remain available in the face of a network problem

Thus, According to CAP theorem, applications that don’t require linearizability, can be more tolerant of network problems, because it can remain available in the face of them.

The CAP theorem doesn’t say thing about network delays, dead nodes, or other trade-offs. Thus, although CAP has been historically influential, it has little practical value for designing systems.

Linearizability and Performance

Although linearizability is a useful guarantee, few systems are actually linearizable in practice, as it is always slow even when there is no network fault, which decreases the performance significantly.

Implementing Linearizable Systems

We can implement Linearizable in two ways

-

Atomic operations + Single Copy (Not good one due to tolerate faults): which only one centralized database. If there are several requests waiting to be handled, but the datastore ensures that every request is handled atomically at a single point in time, acting on a single copy of the data, along a single timeline, without any concurrency.

- To implement linearizability with fault-tolerance we need either a single-leader replicated system, or to use consensus algorithms like zookeeper do (like two-phase commit algorithm)

-

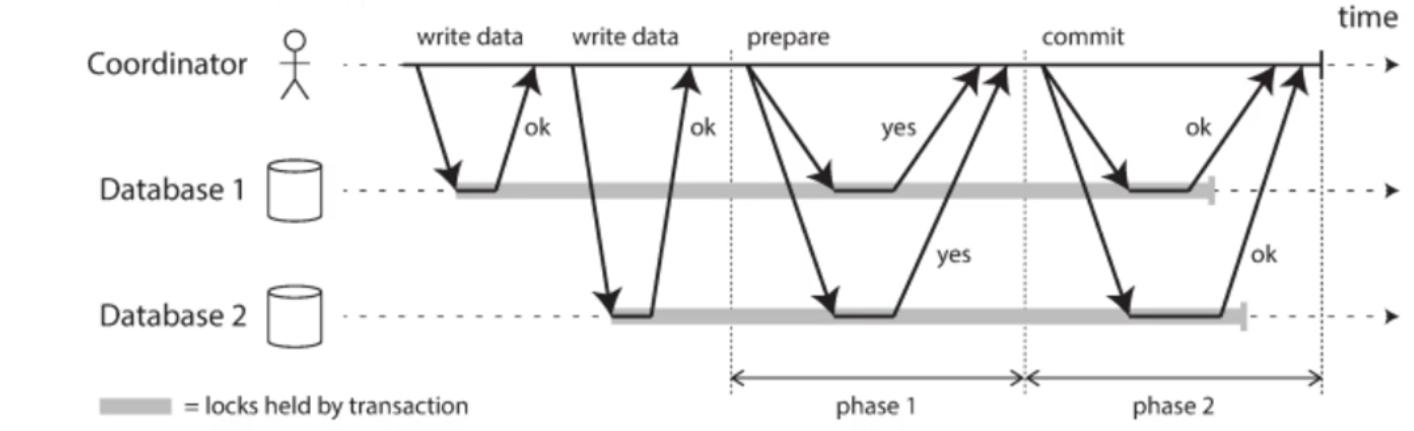

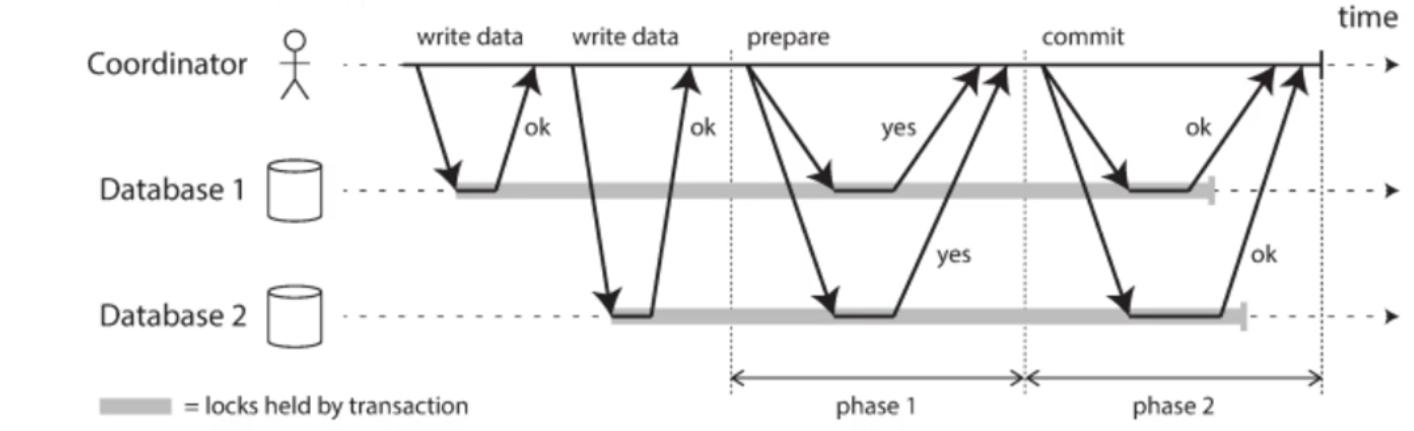

Two Phase commit: there is a coordinator tell the replicas that we need to write data, should all replicas reply with Ok, then go into two phases (Prepare and Commit)

- Note for confusing: Two Phase commit 2PC (Linearizability) is not Two Phase Locking 2PL (Serializability)

Ordering Guarantees

Causality imposes an ordering on events: cause comes before effect; a message is sent before that message is received; the question comes before the answer.

Ordering helps preserve causality, and a system that obeys the order imposed by causality is called causally consistent (eg. snapshot isolation provides causal consistency ). When you read from the database, and you see some piece of data, then you must also be able to see any data that causally precedes it.

Causality uses partial order, where concurrent operations may be processed in any order, but non-concurrent operations must be ordered. This is weaker than linearizability which uses total order, where it allows any two elements to be compared and ordered.

Any system that is linearizable will preserve causality correctly. Linearizability doesn’t have concurrent operations, however, it is one of the ways of preserving causality.

A system can be causally consistent without incurring the performance hit of making it linearizable (CAP theorem doesn’t apply). Causal consistency is the strongest possible consistency model that doesn’t slow down or fail due to network failures or delays.

Researchers are exploring new kinds of databases that preserve causality, with performance and availability characteristics that are similar to those of eventually consistent systems.

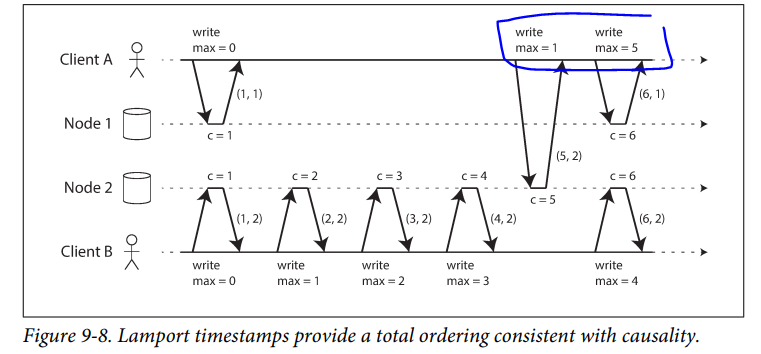

Causal consistency needs to track causal dependencies across the entire database, not just for a single key, so version vectors can be used for that. However, keeping track of all dependencies can become impractical, so a better way could be to use sequence numbers or timestamps (from a logical clock) to order events instead. These numbers are compact and provide a total order.

Sequence Number Ordering

In a database with single-leader replication, the replication log defines a total order of write operations that is consistent with causality. The leader can simply increment a counter for each operation, and thus assign a monotonically increasing sequence number to each operation in the replication log. If a follower applies the writes in the order they appear in the replication log, the state of the follower is always causally consistent (even if it is lagging behind the leader).

The best known way of generating sequence numbers for causal consistency is Lamport timestamps, where every node and every client keeps track of the maximum counter value it has seen so far, and includes that maximum on every request. When a node receives a request or response with a maximum counter value greater than its own counter value, it immediately increases its own counter to that maximum.

As long as the maximum counter value is carried along with every operation, this scheme ensures that the ordering from the Lamport timestamps is consistent with causality, because every causal dependency results in an increased timestamp.

The advantage of Lamport timestamps over version vectors is that they are more compact. The difference between Lamport timestamps and version vectors, is that version vectors can distinguish whether two operations are concurrent or weather one is causally dependent on the other, whereas Lamport timestamps always enforce total ordering. Lamport timestamps are more compact, but we cannot use it to tell whether two operations are concurrent or casually dependent.

In order to use total ordering between multiple nodes, we should use total order broadcast, which is a message exchanging protocol that guarantees reliability (no messages are lost), and total ordered delivery of messages to all nodes.

Consensus services such as ZooKeeper and etcd actually implement total order broadcast. This fact is a hint that there is a strong connection between total order broadcast and consensus, which we will explore later in this chapter.

Total order broadcast is exactly what you need for database replication: if every message represents a write to the database, and every replica processes the same writes in the same order, then the replicas will remain consistent with each other (aside from any temporary replication lag). This principle is known as state machine replication.

An important aspect of total order broadcast is that the order is fixed at the time the messages are delivered: a node is not allowed to retroactively insert a message into an earlier position in the order if subsequent messages have already been delivered. This fact makes total order broadcast stronger than timestamp ordering

Total order broadcast is used in database replication, serializable transactions, creating messages log, and lock for fencing tokens.

Implementing linearizable storage using total order broadcast

Total order broadcast is asynchronous: messages are guaranteed to be delivered reliably in a fixed order, but there is no guarantee about when a message will be delivered (so one recipient may lag behind the others). By contrast, linearizability is a recency guarantee: a read is guaranteed to see the latest value written.

You can build linearizable storage on top of it. For example, you can ensure that usernames uniquely identify user accounts.

You can Implement it using atomic compare-and-set operation. Every register initially has the value null and when a user wants to create a username, you execute a compare-and-set operation on the register for that username, setting it to the user account ID.

You can implement it by using total order broadcast using append-only log:

- Append a message to log indicating the username

- Read the log and wait for the message you appended to be delivered back to you

- Check for any messages claiming the username that you want. If the first message for your desired username is your own message, then you are successful: you can commit the username claim (perhaps by appending another message to the log) and acknowledge it to the client. If the first message for your desired username is from another user, you abort the operation.

The above guarantee linearizable writes not reads. To make reads linearizable, there are a few options:

- Performing the actual read when the message is delivered back to you.

- If the log allows you to fetch the position of the latest log message in a linearizable way, you can query that position, wait for all entries up to that position to be delivered to you, and then perform the read.

Implementing total order broadcast using linearizable storage

The algorithm is simple: for every message you want to send through total order broadcast, you increment-and-get the linearizable integer, and then attach the value you got from the register as a sequence number to the message. You can then send the message to all nodes (resending any lost messages), and the recipients will deliver the messages consecutively by sequence number.

Distributed Transactions and Consensus

Consensus is one of the most important and fundamental problems in distributed computing. On the surface, it seems simple: informally, the goal is simply to get several nodes to agree on something. You might think that this shouldn’t be too hard. Unfortunately, many broken systems have been built in the mistaken belief that this problem is easy to solve.

Important situations we need the nodes to agree.

- Leader Election: all nodes need to agree on which node is the leader. The leadership position might become contested if some nodes can’t communicate with others due to a network fault. So split brain problem happen in which two nodes believe themselves to be the leader.

- Atomic Commit: In database supports transactions over several nodes or partitions, we have the problem that a transaction may fail on some nodes but succeed on others. we have to get all nodes to agree on the outcome of the transaction.

Atomic Commit and Two-Phase Commit (2PC)

the most common way of solving atomic commit and which is implemented in various databases, messaging systems, and application servers. It turns out that 2PC is a kind of consensus algorithm but not a very good one (we will discuss later other consensus algorithms used in ZooKeeper and etcd).

Atomic commit is easy on a single node and implemented by default by storage engine, as it just depends on the order in which data is durably written to disk.

but it’s quite challenging when performed across multiple nodes involved in a transaction (multi-object transaction in partitioned database), as it’s not sufficient to send a commit request to all nodes independently. Most NoSQL datastores don’t support such transactions, but various relational systems do.

If some nodes commit the transaction but others abort it, the nodes become inconsistent with each other. A transaction commit must be irrevocable—you are not allowed to change your mind and retroactively abort a transaction after it has been committed. The reason for this rule is that once data has been committed, it becomes visible to other transactions, and thus other clients may start relying on that data.

Two-phase commit is an algorithm for achieving atomic transaction commit across multiple nodes to ensure that either all nodes commit or all nodes abort.

2PC is used internally in some databases, Java Transaction API and WSAtomicTransaction for SOAP web services.

The 2PC protocol contains two crucial points of “no return”, when a participant votes yes in the prepare phase, and when the coordinator decides the decision. The decision is irrevocable, but could be undone by another compensating transaction.

Coordinator is often implemented as a library within the same application process that is requesting the transaction (e.g., embedded in a Java EE container), but it can also be a separate process or service. Examples of such coordinators include Narayana, JOTM, BTM, or MSDTC.

A 2PC transaction begins with the application reading and writing data on multiple database nodes, as normal. We call these database nodes participants in the transaction. When the application is ready to commit, the coordinator begins phase 1: it sends a prepare request to each of the nodes, asking them whether they are able to commit. The coordinator then tracks the responses from the participants:

- If all participants reply “yes,” indicating they are ready to commit, then the coordinator sends out a commit request in phase 2, and the commit actually takes place.

- If any of the participants replies “no,” the coordinator sends an abort request to all nodes in phase 2.

The steps in more details

- When the application wants to begin a distributed transaction, it requests a transaction ID from the coordinator.

- App start single-node transaction in each node with transaction ID, all reads and writes are done. If any failure happened, the coordinator abort transaction

- When application is ready to commit, coordinator sends prepare request to all participants.

- When a participant receives the prepare request, it makes sure that it can definitely commit the transaction under all circumstances. This includes writing all transaction data to disk any conflicts or constraint violations.

- When the coordinator has received responses to all prepare requests, it makes a definitive decision on whether to commit or abort the transaction (committing only if all participants voted “yes”).

- Once the coordinator’s decision has been written to disk, the commit or abort request is sent to all participants. If this request fails or times out, the coordinator must retry forever until it succeeds.

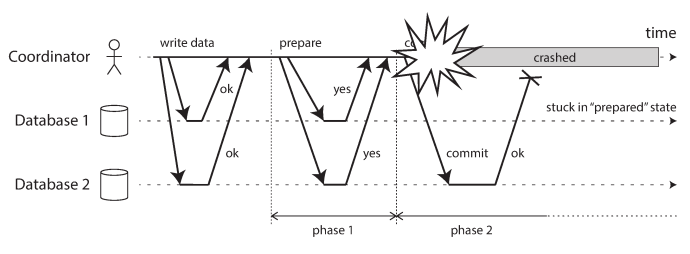

Coordinator failure

If the coordinator fails before sending the prepare requests, a participant can safely abort the transaction. But once the participant has received a prepare request and voted “yes,” it can no longer abort, it must wait to hear back from the coordinator whether the transaction was committed or aborted. If the coordinator crashes or the network fails at this point, the participant can do nothing but wait. A participant’s transaction in this state is called in doubt or uncertain.

The coordinator crashes after participants vote “yes.” Database 1 does not know whether to commit or abort. Without hearing from the coordinator, the participant has no way of knowing whether to commit or abort. In principle, the participants could communicate among themselves to find out how each participant voted and come to some agreement, but that is not part of the 2PC protocol.

A 3PC algorithm can solve this issue in theory but not in practice.

Distributed Transactions in Practice

Some implementations of distributed transactions carry a heavy performance penalty for example, distributed transactions in MySQL are reported to be over 10 times slower than single-node transactions, so it is not surprising when people advise against using them. Much of the performance cost inherent in two-phase commit is due to the additional disk forcing (fsync) that is required for crash recovery, and the additional network round-trips.

Two types of distributed transactions

- Database-internal distributed transactions: Some distributed databases (i.e., databases that use replication and partitioning in their standard configuration) support internal transactions among the nodes of that database. For example, VoltDB and MySQL Cluster’s NDB storage engine have such internal transaction support. In this case, all the nodes participating in the transaction are running the same database software.

- Heterogeneous distributed transactions: In a heterogeneous transaction, the participants are two or more different technologies: for example, two databases from different vendors, or even nondatabase systems such as message brokers. A distributed transaction across these systems must ensure atomic commit, even though the systems may be entirely different under the hood.

Database internal apply optimizations since uses the same database software.

Exactly-once message processing

Heterogeneous distributed transactions allow diverse systems to be integrated in powerful ways. For example, a message from a message queue can be acknowledged as processed if and only if the database transaction for processing the message was successfully committed.

The side effect of using message broker may safely redeliver the message later if transaction failed and this ensure that the message is effectively processed exactly once.

XA transactions

X/Open XA (short for eXtended Architecture) is a standard for implementing two-phase commit (2PC) across heterogeneous technologies. XA is supported by many traditional relational databases (including PostgreSQL, MySQL, DB2, SQL Server, and Oracle) and message brokers (including ActiveMQ, HornetQ, MSMQ, and IBM MQ).

XA is not a network protocol—it is merely a C API for interfacing with a transaction coordinator. The transaction coordinator implements the XA API as a client library. It keeps track of the participants in a transaction, collects partipants’ responses after asking them to prepare (via a callback), and uses a log on the local disk to keep track of the commit/abort decision for each transaction.

Holding locks while in doubt

The database cannot release those locks until the transaction commits or aborts. Therefore, when using two-phase commit a transaction must hold onto the locks throughout the time it is in doubt. If the coordinator has crashed and takes 20 minutes to start up again, those locks will be held for 20 minutes. If the coordinator’s log is entirely lost for some reason, those locks will be held forever—or at least until the situation is manually resolved by an administrator.

The problem with transaction that is stuck waiting for coordinator, is that it cannot release the locks it’s holding, which can cause larger parts of the application to become unavailable. This can be fixed by either a human manual interaction, or using an automated heuristic decisions.

Limitations of distributed transactions

XA transactions solve the real and important problem of keeping several participant data systems consistent with each other, but as we have seen, they also introduce major operational problems.

- If the coordinator is not replicated but runs only on a single machine, it is a single point of failure for the entire system

- Many server-side applications are developed in a stateless model with all persistent state stored in a database, which has the advantage that application servers can be added and removed at will. However, when the coordinator is part of the application server, it changes the nature of the deployment. Suddenly, the coordinator’s logs become a crucial part of the durable system state—as important as the databases themselves, since the coordinator logs are required in order to recover in-doubt transactions after a crash. Such application servers are no longer stateless.

- Since XA needs to be compatible with a wide range of data systems, it is necessarily a lowest common denominator. For example, it cannot detect deadlocks across different systems

- For database-internal distributed transactions (not XA), the limitations are not so great—for example, a distributed version of SSI is possible.

There are alternative methods that allow us to achieve the same thing without the pain of heterogeneous distributed transactions. We will return to these in Chapters 11 and 12.

Consensus algorithm in a formalized form should satisfy 4 properties: all nodes should agree on the same decision, no node decides twice, if a node decides a value, then the value must have been proposed by some node, and every non-crashed node should eventually decide some value. However, for the last property to be guaranteed, the algorithm requires at least the majority of the nodes to be functioning correctly.

The best known fault-tolerance consensus algorithms are Viewstamped Replication, Paxos, Raft, and Zab. All of them (except Paxos) implement total order broadcast directly, as total order broadcast is equivalent to repeated rounds of consensus.

All consensus protocols use a leader internally, but don’t guarantee the leader uniqueness, instead a weaker guarantee is to only guarantee the leader uniqueness within each epoch (lifetime of a leader). Thus, we end-up having two round of voting, once to choose a leader, and a second to vote on leader’s proposal.

Some limitations of consensus algorithms include: it requires a strict majority to operate, it assumes a fixed set of nodes to participate in voting, it generally relies on timeouts to detect failed nodes, and it’s sensitive to network problems.

Membership and Coordination Services

Projects like ZooKeeper or etcd are often described as “distributed key-value stores” or “coordination and configuration services.” The API of such a service looks pretty much like that of a database: you can read and write the value for a given key, and iterate over keys. So if they’re basically databases, why do they go to all the effort of implementing a consensus algorithm? What makes them different from any other kind of database?

As an application developer, you will rarely need to use ZooKeeper directly, because it is actually not well suited as a general-purpose database. It is more likely that you will end up relying on it indirectly via some other project: for example, HBase, Hadoop YARN, OpenStack Nova, and Kafka all rely on ZooKeeper running in the background.

ZooKeeper and etcd are designed to hold small amounts of data that can fit entirely in memory. That small amount of data is replicated across all the nodes using a fault-tolerant total order broadcast algorithm.

ZooKeeper is modeled after Google’s Chubby lock service implementing not only total order broadcast but also an interesting set of other features that turn out to be particularly useful when building distributed systems like:

- Linearizable atomic operations: Using an atomic compare-and-set operation, you can implement a lock if several nodes concurrently try to perform the same operation, only one of them will succeed.

- Total ordering of operations: when some resource is protected by a lock or lease, you need a fencing token to prevent clients from conflicting with each other in the case of a process pause. The fencing token is some number that monotonically increases every time the lock is acquired. ZooKeeper provides this by totally ordering all operations and giving each operation a monotonically increasing transaction ID (zxid) and version number (cversion)

- Failure detection: Clients maintain a long-lived session on ZooKeeper servers, and the client and server periodically exchange heartbeats to check that the other node is still alive. Even if the connection is temporarily interrupted, or a ZooKeeper node fails, the session remains active. However, if the heartbeats end for a duration that is longer than the session timeout, ZooKeeper declares the session to be dead. Any locks held by a session can be configured to be automatically released when the session times out

- Change notifications: Not only can one client read locks and values that were created by another client, but it can also watch them for changes. Thus, a client can find out when another client joins the cluster or if another client fails. By subscribing to notifications, a client avoids having to frequently poll to find out about changes.

Also, ZooKeeper, etcd, and Consul are also often used for service discovery that is, to find out which IP address you need to connect to in order to reach a particular service. However, it is less clear whether service discovery actually requires consensus. DNS is the traditional way of looking up the IP address for a service name, and it uses multiple layers of caching to achieve good performance and availability.