Designing Data Intensive Applications Notes: Ch.8 The Trouble with Distributed Systems

Mohamed Kassem | November 04, 2023

Continuing our series for “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” book.

In this article, we will walkthrough the second chapter of this book Chapter.8 The Trouble with Distributed Systems.

Table Of Content (TOC)

Working with distributed systems is fundamentally different from writing software on a single computer and the main difference is that there are lots of new and excit‐ ing ways for things to go wrong.

Faults and Partial Failures

In a single computer when the hardware is working correctly, the same operation always produces the same result (it is deterministic).

In a distributed system, there may well be some parts of the system that are broken in some unpredictable way, even though other parts of the system are working fine. This is known as a partial failure (nondeterministic).

If we want to make distributed systems work, we must accept the possibility of partial failure and build fault-tolerance mechanisms into the software. This is achieved by knowing what behavior to expect from the software in the case of fault, consider wide range of possible faults, and artificially create such situations in our testing environment to see what happens.

Unreliable Networks

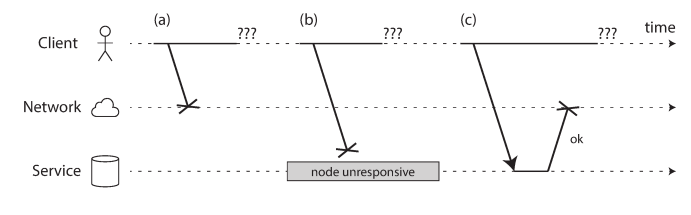

The internet and most internal networks in datacenters (often Ethernet) are asynchronous packet networks. In this kind of network, one node can send a message (a packet) to another node, but the network gives no guarantees as to when it will arrive, or whether it will arrive at all. If you send a request and expect a response, many things could go wrong.

Many systems need to automatically detect faulty nodes, such as load balancers to stop sending requests to a dead node, or a when a leader fails in a single-leader replication. We might be able to get some feedback from the network protocols such as RST or FIN packets, or configure the machine’s operating system to start a script when the process crashes, but these approaches doesn’t gives strong guarantees as compared to receiving feedback from the application itself.

Rapid feedback about a remote node being down is useful, but you can’t count on it. Even if TCP acknowledges that a packet was delivered, the application may have crashed before handling it. If you want to be sure that a request was successful, you need a positive response from the application itself

Timeouts and Unbounded Delays

Declaring a node dead is problematic, A long timeout means a long wait until a node is declared dead. A short timeout detects faults faster but carries a higher risk of incorrectly declaring a node dead when in fact it has only suffered a temporary slowdown.

Theoretically, a reasonable timeout value is 2d + r, where d is the maximum delay for a packet, and r is the node’s processing time. However, these values are hardly bounded in practice. So, choosing the timeouts by continuous experimental measurements is usually better (jitter). This is happened in AWS, AKKA, Cassandra.

Some latency-sensitive applications, use UDP rather than TCP, as it’s a good choice in situations where delayed data is worthless like in VoIP phone call, Live streaming.

Ethernet and IP are packet-switched protocols not circuit-switching which suffer from queueing and thus unbounded delays in the network.

Unreliable Clocks

It’s hard to define the time inside a distributed system, as each machine has its own notion of time, which maybe slightly faster or slower than others. Network Time Protocol (NTP) is commonly used to solve this problem. Which allows the computer clock to be adjusted according to the time reported by a group of servers. The servers in turn get their time from a more accurate time source, such as a GPS receiver.

Modern computers have at least two different kinds of clocks:

- Time-of-delay clock, which is usually synchronized with NTP to return the current date and time, but it is unsuitable for measuring elapsed time.

- Monotonic clock, which is guaranteed to always move forward, therefore suitable for measuring duration (eg. timeouts), but has a meaningless absolute value. It also may use NTP to adjust its frequency: how fast it moves forward.

In a distributed system, using a monotonic clock for measuring elapsed time (e.g.,timeouts) is usually fine, because it doesn’t assume any synchronization between different nodes’ clocks and is not sensitive to slight inaccuracies of measurement

Unfortunately, our methods for getting a clock to tell the correct time aren’t nearly as reliable or accurate. However, we can manage to get a good enough accuracy using GPS receivers, Precision Time Protocol (PTP), and careful deployment and monitoring. Such monitoring ensures that we notice broken clocks before they cause too much damage.

Robust software needs to be prepared to deal with incorrect clocks.

NTP synchronization can’t insure correct ordering of events in distributed systems. Thus, an additional causality tracking mechanisms, such as logical clocks (eg. version vectors), is safer alternative.

The best possible time accuracy in practice is probably to the tens of milliseconds, so it might be better to define time within a range of lower to higher possible values. This uncertainty bound can be calculated based on the time source.

Threads can pause for long period of time for multiple reasons (eg. garbage collection), in this period it loses sense of time. So a node in a distributed system must expect such pause even in a middle of a function, and encounter for it.

Knowledge, Truth, and Lies

In a distributed system, a node cannot know anything for sure, but we can state the assumptions we are making about the behavior (the system model), and algorithms can be proved to function correctly within certain system models.

A node cannot trust its own judgment, and must abide by the voting (quorum) decision of other nodes, even if it only effects itself.

When using lock or lease to protect access to some resource, a mechanism such as fencing should be enforced to prevent a node that falsely believe it has the access, from disrupting the rest of the system. It’s unwise for a service to assume that its clients will always behave well.

Distributed systems problems become much harder if there is a risk that nodes may lie, such a behavior is known as Byzantine fault, and a system is byzantine fault-tolerant if it continues to operate correctly even if some nodes are malfunctioning or under malicious attack.

Byzantine fault-tolerant algorithms are quite complicated and costly to deploy, making them impractical, especially when all nodes are running inside the companies datacenters, but it might make sense in a peer-to-peer network.

Even if we trust our nodes, there is still a weak form of lying, such as hardware issues, software bugs, or misconfiguration. Luckily, we can tolerate this using checksum on TCP or application level for example, and by input validation.

System models with regards to timing includes:

- Synchronous model, which is not realistic as it assumes delays never exceeds an upper bound

- Partially synchronous model however assumes the system to behave synchronously only for most of the time, which is realistic

- Asynchronous model which makes no assumptions about timings, but it’s very restrictive

And from node failure perspective, system models include:

- Crash-stop-faults, where node only fails when it crashes, thereafter its gone forever

- Crash-recovery-faults, where the node can crash at any moment, but perhaps respond again after some unknown time

- Byzantine-faults, where nodes can do anything including trying to trick other nodes

The most useful model in real systems is the partially synchronous model with crash-recovery.

It’s important to distinguish between two kind of properties, safety and liveness, because it is common to require that safety properties always hold, while with liveness properties we are allowed to make caveats.

We do have to make some assumptions about faults that can happen. However, real implementation might still have to handle impossible cases, even by just firing an error message.