Designing Data Intensive Applications Notes: Ch.7 Transactions

Mohamed Kassem | November 04, 2023

Continuing our series for “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” book.

In this article, we will walkthrough the second chapter of this book Chapter.7 Transactions.

Table of Content (TOC)

Things that will go wrong with your application

- The application or database will fail in the middle of a write operation

- Interruptions in the network will cut off the application from the database

- Several clients will write/read to the database at the same time, overwriting each other’s changes

- A client will read data that doesn’t make sense because it has only partially been updated

- Race conditions will keep happening.

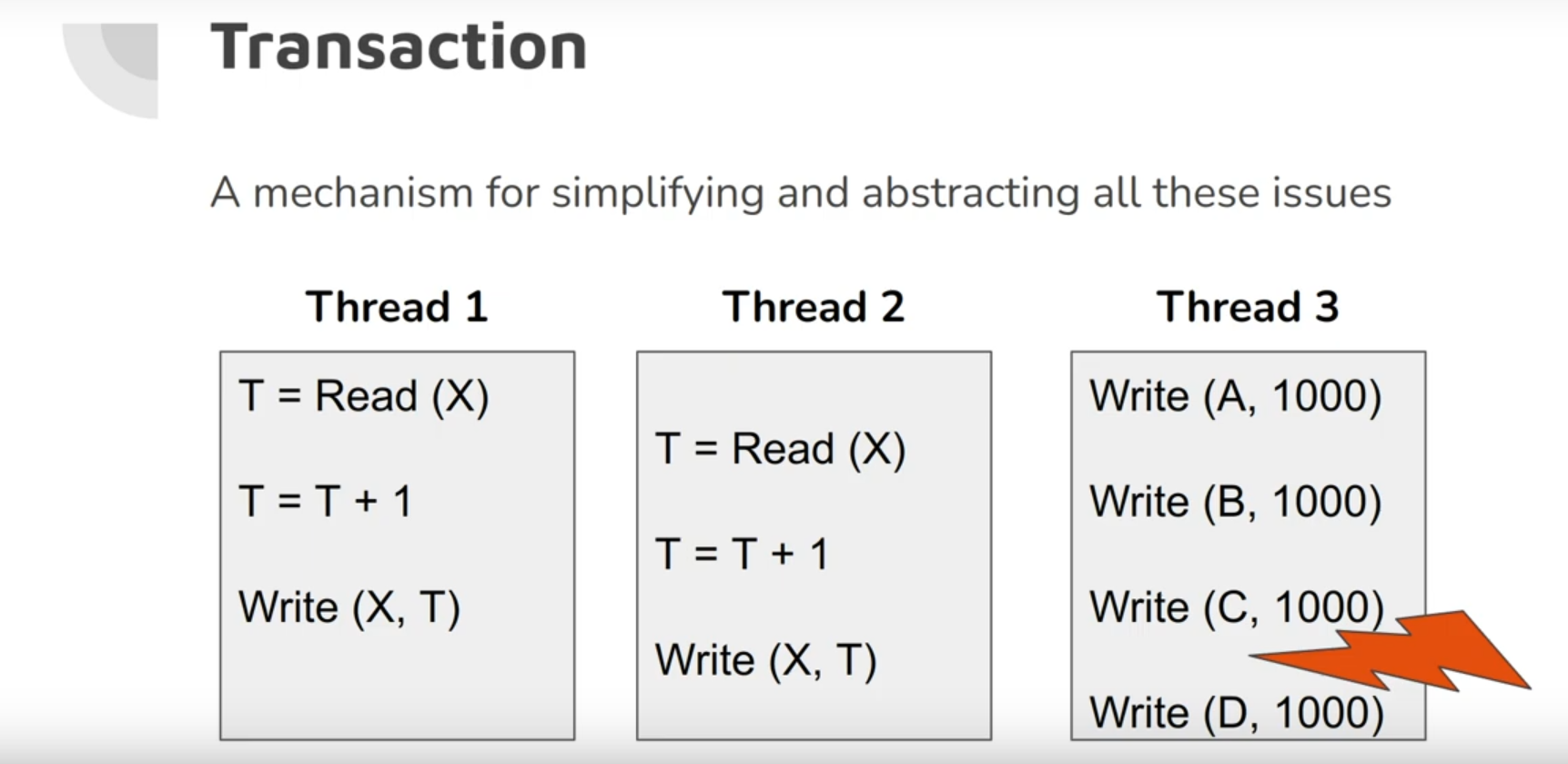

To solve these issues we will use Transactions.

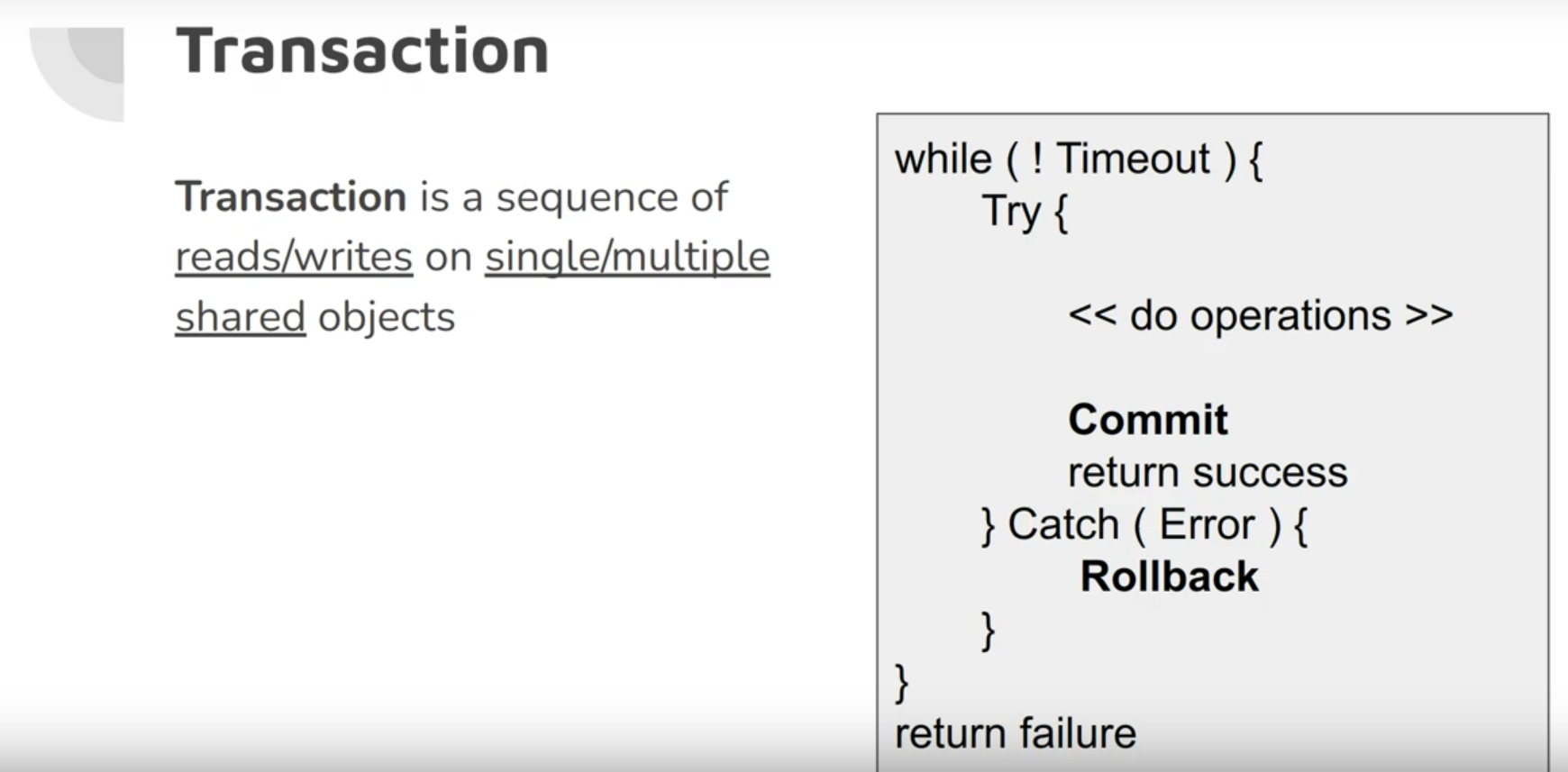

A transaction is a way for an application to group several reads and writes together into a logical unit. Conceptually, all the reads and writes in a transaction are executed as one operation: either the entire transaction succeeds (commit) or it fails (abort, rollback)

By using transactions, the application is free to ignore certain potential error scenarios and concurrency issues, because the database takes care of them instead (we call these safety guarantees (which treat them as synchronized operations)).

This chapter discusses area of concurrency control, various kinds of race conditions, and how databases implement isolation levels such as read committed, snapshot isolation, and serializability.

Transactions support most relational databases like MySQL, PostgreSQL, Oracle, SQL Server, and some non-relational databases.

The Slippery Concept of a Transaction

There are wrong misconceptions that any large system should abandon transactions in order to maintain good performance and high availability, and that transactions are essential to database vendors, but these viewpoints are pure hyperbole.

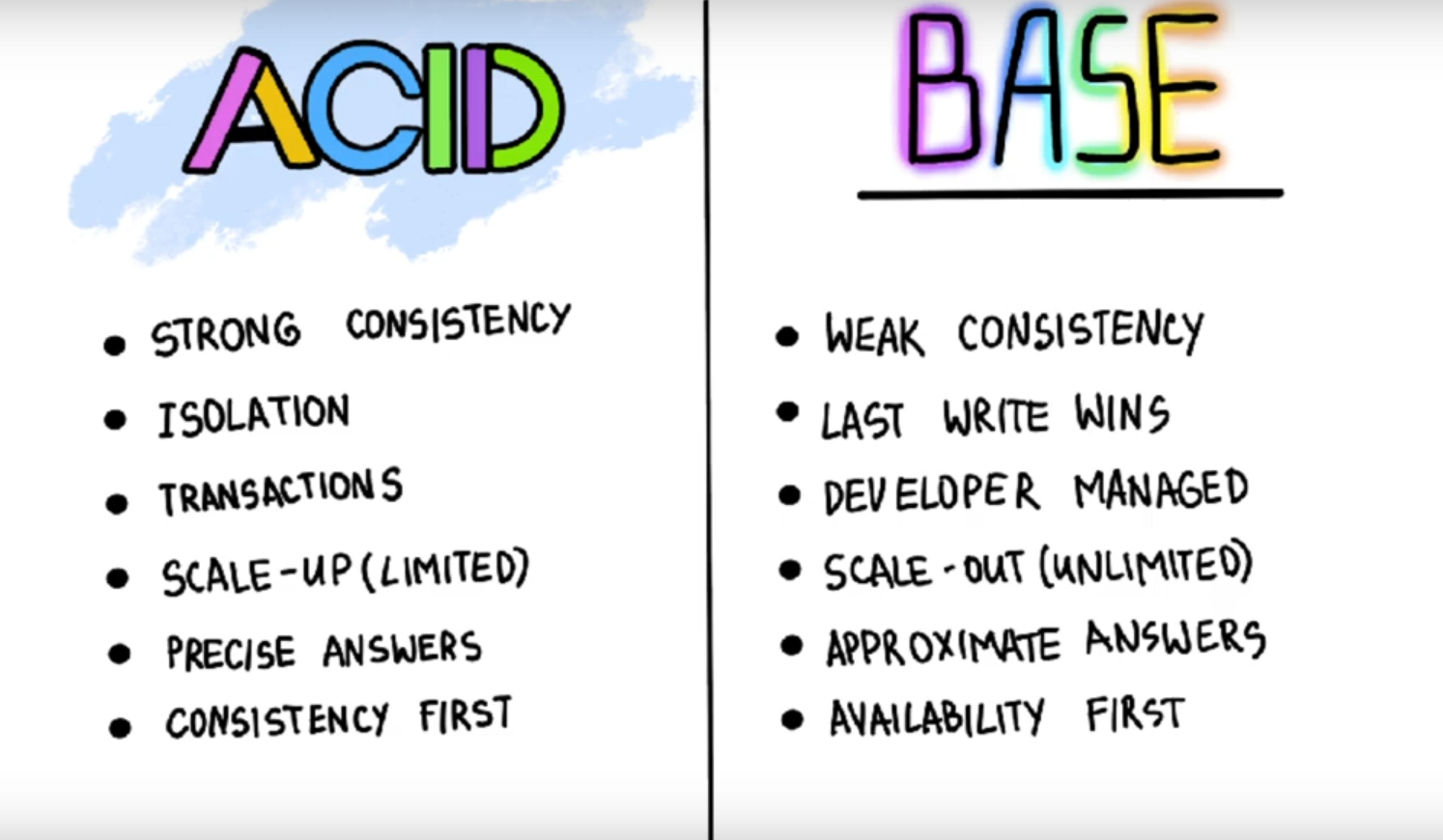

There are two mechanisms to achieve this ACID (Atomicity + Consistency + Isolation + Durability ) and its inverse called BASE (Basically Available + Soft state + Eventual Consistency)

ACID

To achieve safety guarantees, this is described by ACID which stands to Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, and durability.

Systems that do not meet the ACID criteria are sometimes called BASE, which stands for Basically Available, Soft state, and Eventual consistency. This is even more vague than the definition of ACID. It seems that the only sensible definition of BASE is “not ACID”; i.e., it can mean almost anything you want

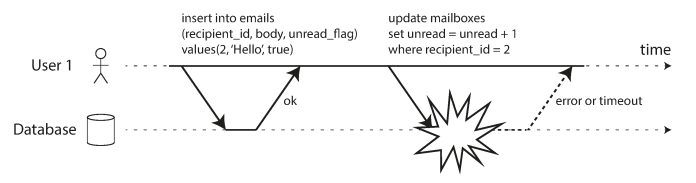

Atomicity

Refers to something that cannot be broken down into smaller parts, so when a client wants to make several writes, but a fault occurs, the whole transaction aborts/is discarded by the database, and the client can safely retry.

- ALL or None: The system can only be in the state it was during the operation or after the operation. not something in between.

- Failure guarantee

The following diagram illustrates that Atomicity ensures that if an error occurs any prior writes from that transaction are undone, to avoid an inconsistent state.

Consistency

Insert only valid data and that the database is being in a “good-state”, which is not something the application should guarantee, not the database.

- Data should make sense (domain-specific: twitter vs banking system)

- Semantic guarantee

Isolation

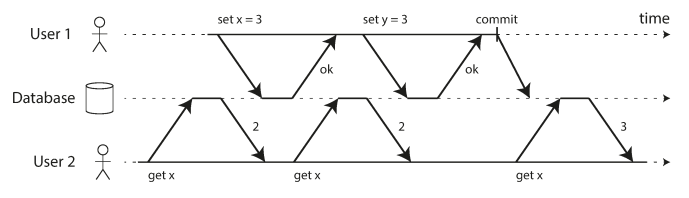

- Each transaction can not see what is happening now inside any other concurrent transaction till they finish.

- Implemented using locks

- Concurrency guarantee

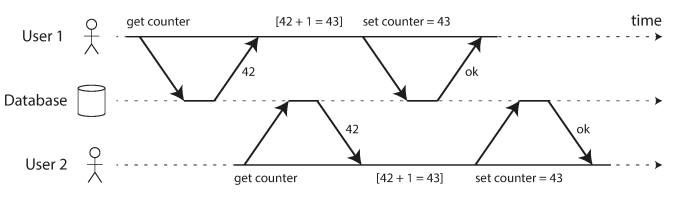

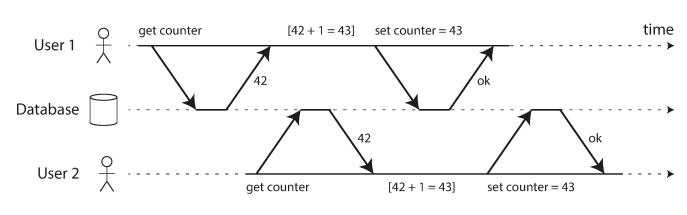

The following example showing a race condition problem that they are reading the same data at the same time.

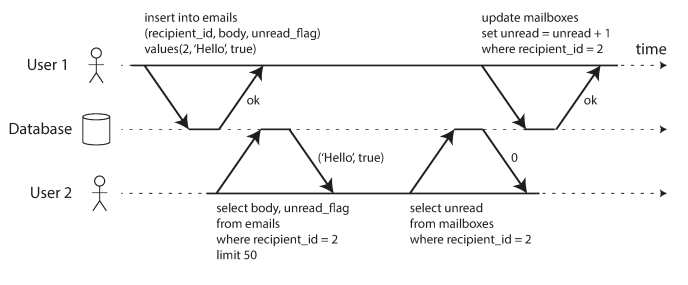

Another example shows violating isolation: one transaction reads another transaction’s uncommitted writes (a “dirty read”).

To Fix this: we use Isolation

Durability

- Any data it has written successfully will not be forgotten, even if there is a hardware fault or database crashes.

- Implemented using write-ahead-log or replication

- Reliability guarantee (perfect durability does not exist)

BASE

good reference: https://neo4j.com/blog/acid-vs-base-consistency-models-explained/

- Basically Available: The system appears to work most of the time.

-

Soft State:

- We don’t have to be write-consistent (eg. read your own writes) or mutually consistent (between replicas) all time.

- The state the user put into the system that will go away (expire) if user doesn’t maintain (refresh) it. your system depends on the external user factor by using refresh

- Eventual Consistency: the system will become consistent over time, given that the system doesn’t receive input during that time.

Storage engines almost universally aim to provide atomicity and isolation on the level of single object. Atomicity can be implemented using log for crash recovery, and isolation using a lock on each object.

Multi-object transactions might be needed when a foreign key references to a row in another table, or when de-normalized information and secondary indexes needs to be updated. However, many distributed datastores abandoned multi-object transactions because they are difficult to implement across partitions.

Leaderless replicated datastores won’t undo something it has already done, so it’s the application’s responsibility to recover from errors.

Retrying aborted transactions isn’t perfect

- because If the transaction actually succeeded but the network failed while the server is trying to acknowledge the successful commit (so the client thinks it failed), the transaction might get performed twice.

- If the error is due to overload, retrying the transaction will make the problem worse, not better. To avoid such feedback cycles, you can limit the number of retries, use exponential backoff, and handle overload-related errors differently from other errors (if possible)

- It is only worth retrying after transient errors (for example due to deadlock, isolation violation, temporary network interruptions, and failover); when the error is permanent (eg. constraint violation), retrying would be pointless.

Weak Isolation Levels

Concurrency issues (race conditions) only come into play when one transaction reads data that is concurrently modified by another transaction, or when two transactions try to simultaneously modify the same data.

Serializable isolation means that the database guarantees that transactions have the same effect as if they ran serially (i.e., one at a time, without any concurrency).

Concurrency bugs are hard to find by testing, for that, databases have long tried to hide it by providing transaction isolation, especially serializable isolation. However, due to its performance cost, systems use weaker levels of isolations more commonly, which protect against some concurrency issues, but not all. Many popular relational databases that are considered “ACID” use weak isolation themselves.

Read Committed

The most basic level of transaction isolation is read committed.v It makes two guarantees:

- When reading from the database, you will only see data that has been committed (no dirty reads).

- When writing to the database, you will only overwrite data that has been committed (no dirty writes)

No dirty reads

Imagine a transaction has written some data to the database, but the transaction has not yet committed or aborted. Can another transaction see that uncommitted data? If yes, that is called a dirty read

The following example prevents dirty reads

No dirty writes

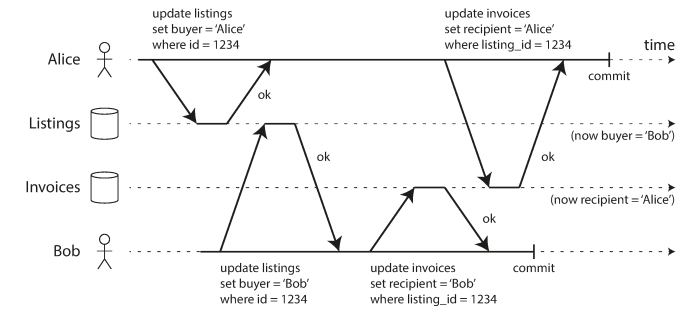

Dirty writes is when a transaction write overwrites another transaction’s uncommitted write, this is useful because if the transaction updates multiple objects, dirty writes can lead to bad outcome, however, preventing it still doesn’t prevent some other race conditions. Most databases prevents dirty writes by using row-level locks.

The following example shows dirty writes

The following example shows it still doesn’t prevent race conditions which that the second transaction happened after first one has committed (which means that there are no dirty writes) but still incorrect behavior. in “Preventing Lost Updates” we will discuss how to make such counter increments safe.

How to implement it?

Read committed is a very popular isolation level. It is the default setting in Oracle 11g, PostgreSQL, SQL Server 2012, MemSQL, and many other databases.

-

To Prevent Dirty Writes

- Transaction acquire write lock (exclusive)

-

To Prevent Dirty Reads

-

Acquire write lock and immediately release it. This would ensure that a read couldn’t happen while an object has a dirty, uncommitted value (because during that time the lock would be held by the transaction that has made the write)

- The issue with this approach that may write transaction can take long time and hold the other reads to wait the writers to finish.

- Another approach that most databases do is keeps 2 versions of each object value (committed and overwritteen-but-not-yet-committed) like the image in preventing dirty reads.

-

Snapshot Isolation (Repeatable Read)

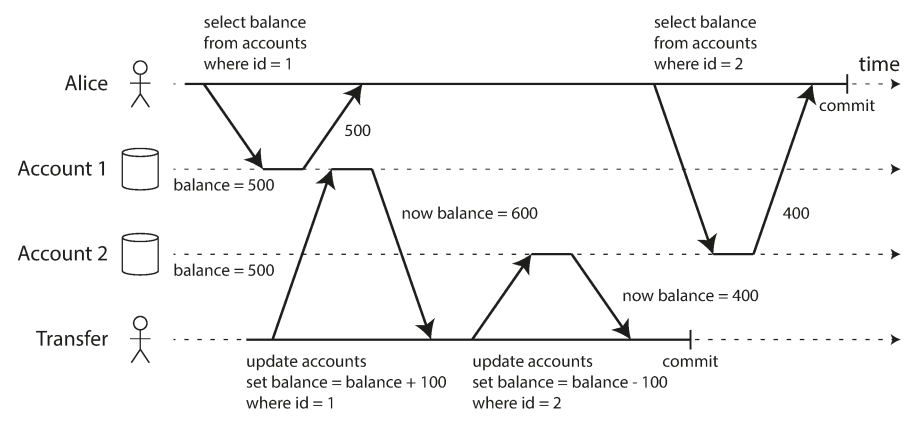

Read committed isolation doesn’t protect against read skew, where a transaction reads different parts from the database in different points of time.

The following example explain Read skew (non repeatable read) problem which shows that Alice do transfer transaction between her two accounts. but when she see the two lists at the same time, she seen inconsistent state (one still with 500$ and the other account with 400$ so the total is $900 in her accounts—it seems that $100 has vanished into thin air)

Other examples for Read skew (non repeatable read) problem:

- Taking Backups: Taking a backup requires making a copy of the entire database, which may take hours on a large database. During the time that the backup process is running, writes will continue to be made to the database. Thus, you could end up with some parts of the backup containing an older version of the data, and other parts containing a newer version. If you need to restore from such a backup, the inconsistencies (such as disappearing money) become permanent

- Executing Analytics query

- Doing integrity checks

Snapshot isolation is the most common solution to this problem, where each transaction reads from a consistent snapshot of the database (only committed data at the beginning of transaction), as if it was frozen at a particular point in time.

Snapshot isolation is useful for read only queries like backups and analytics. this popular features is supported by PostgreSQL, MySQL with the InnoDB storage engine, Oracle, SQL Server, and others.

Implementing snapshot isolation

By using write locks and reads do not require any locks. From a performance point of view, a key principle of snapshot isolation is readers never block writers, and writers never block readers.

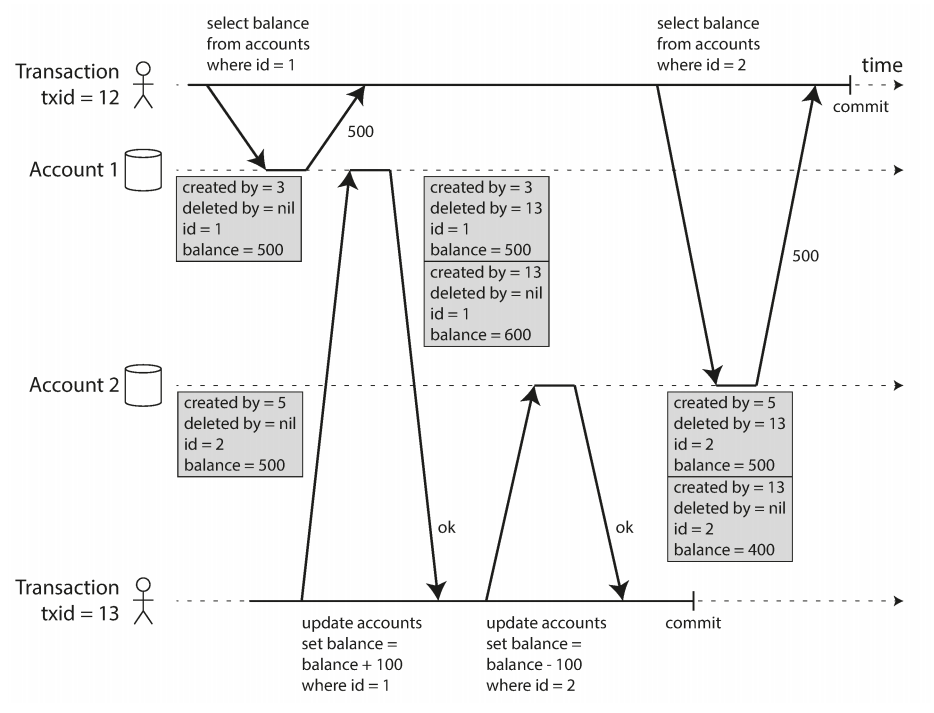

Implemented by Multi-version concurrency control (MVCC) meaning that each object in the database has multi version, because various in-progress transactions may need to see the state of the database at different points in time. When another transaction need to read it will return the data of with version number at this timestamp.

In the above diagram there are two transactions initiated by previous transactions 5 and 3. In any writes the database keep multiple versions of the object according to the transactions. When transaction 12 try again to read the value it will find there two version (one caused by previous transaction 5 and one caused by transaction 13 which happened after me, so it will take any transaction happened before me)

At some later time, when it is certain that no transaction can any longer access the deleted data, a garbage collection process in the database removes any rows marked for deletion and frees their space.

Indexing might sound like a problem for snapshot isolation, but one solution is to have the index point to all versions of an object, while another approach (used in CouchDB) is to use an append-only/copy-on-write variant that doesn’t overwrite pages in the underlying tree.

Preventing Lost Updates

This is happens when two transactions writing concurrently (write-write conflict that can occur).

A common pattern in databases is read-modify-write, which might lead to lost update problem. This problem occur when two concurrent transactions perform read-modify-write cycle, and one of the updates was overridden and lost.

There are variety of solutions that has been developed for solving the lost update problem:

-

Atomic writes: which is usually the best solution if the code can be expressed in terms of operations, that is like

UPDATE counters SET value = value + 1 WHERE key = 'foo';- Atomic operations are implemented by taking a lock on the object when it is read so that no other transaction can read it until the update has been applied.

- Unfortunately, ORMs make it easy to accidentally write code that performs unsafe read-modify-write cycles instead of using atomic operations provided by the database.

- MongoDB provide atomic operations for making local modifications to a part of a JSON document, and Redis provides atomic operations for modifying data structures such as priority queues.

-

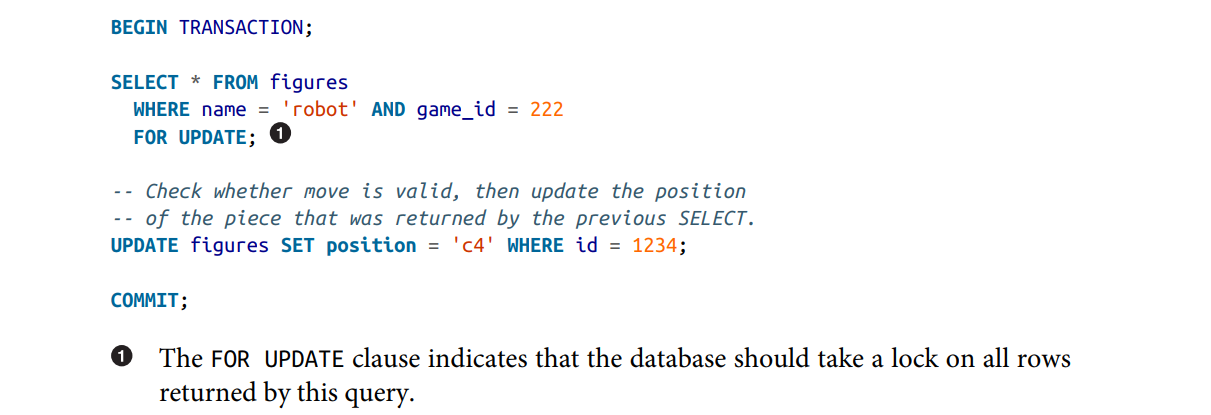

Explicit locking: if the database’s built-in atomic operations don’t provide the necessary functionality, is for the application to explicitly lock objects that are going to be updated. Then the application can perform a read-modify-write cycle, and if any other transaction tries to concurrently read the same object, it is forced to wait until the first read-modify-write cycle has completed.

-

Automatically deleting lost updates: where the database allows the transaction to execute in parallel, and detects a lost update if happened, abort the transaction and force it to retry. An advantage to this is that the database performs the check efficiently in conjunction with snapshot isolation, and the detection happens automatically and is thus less error-prone.

- PostgreSQL’s repeatable read, Oracle’s serializable, and SQL Server’s snapshot isolation levels automatically detect when a lost update has occurred and abort the offending transaction. While MySQL, InnoDB’s repeatable read does not detect lost updates.

- Compare and set: In databases that don’t provide transactions, you sometimes find an atomic compare-and-set CASE(x, Vold, Vnew) operation which allowing an update to happen only if the value has not changed since you last read it.

- Conflict resolution: as in replicated databases, techniques based on locks and compare-set doesn’t apply, so one approach is to allow concurrent writes to create several conflicting versions, and let the application code to resolve (using last write wins) or merge them.

Write Skew

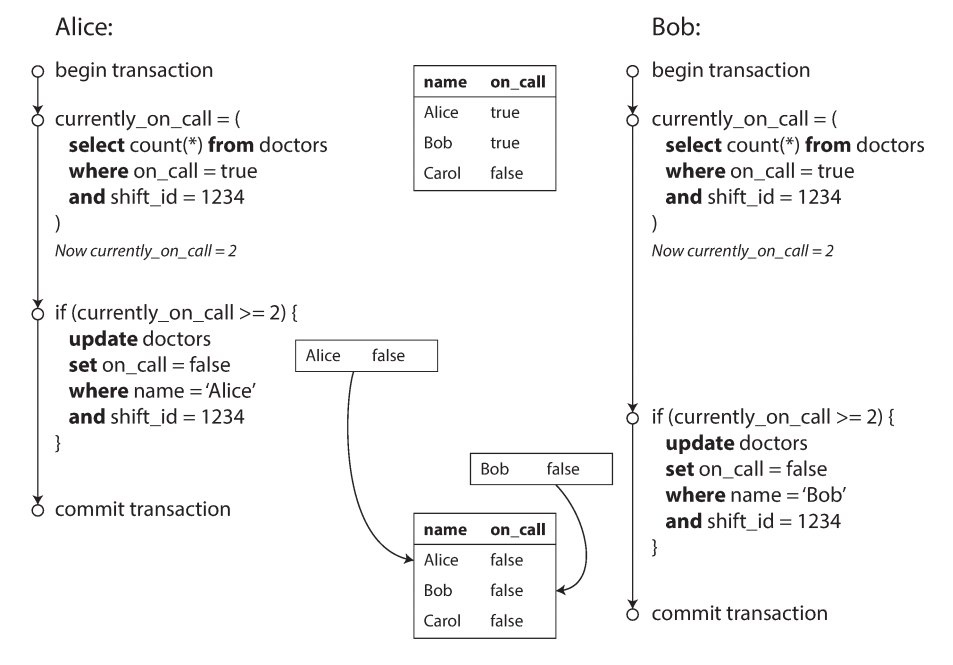

The following example show another race condition problem (write skew) when concurrent writes happened

In each transaction, your application first checks that two or more doctors are currently on call; if yes, it assumes it’s safe for one doctor to go off call. Since the database is using snapshot isolation, both checks return 2, so both transactions proceed to the next stage. Alice updates her own record to take herself off call, and Bob updates his own record likewise. Both transactions commit, and now no doctor is on call.

Write skew can occur if two transactions read the same objects and updating two different objects.

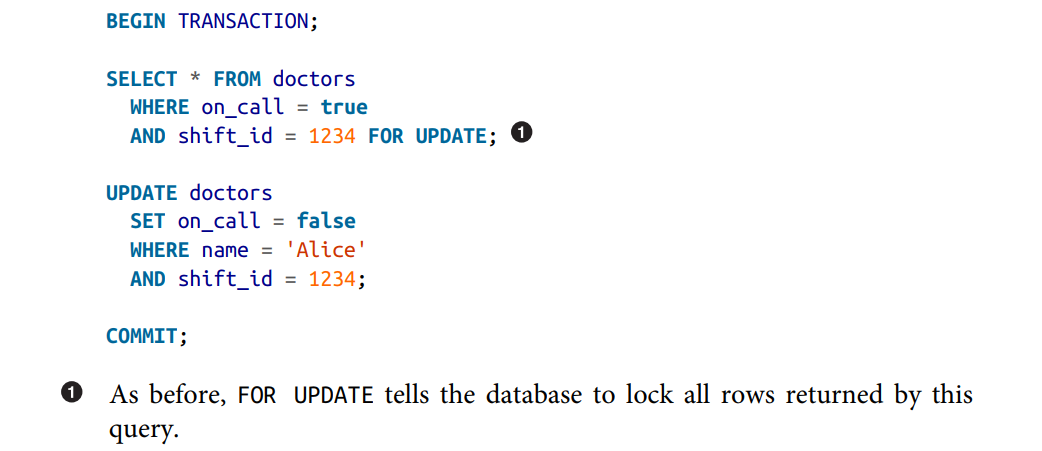

This can be fixed only through

- Serializable isolation

- by configuring some customized constraints with triggers or materialized views as they involve multiple objects

-

or by explicitly lock the rows that the transaction depends on using

FOR UPDATE.

Phantoms

The writes skew always read first then write, Phantom is where a write in one transaction changes the result of a search query in another transaction.

Phantom reads occurs when, in the course of a transaction, new rows are added or removed by another transaction to the records being read, and there is no way to put locks on rows that might not be existing yet. This can be solved using materialized conflicts which is more like an artificial lock to the database. But, serializable isolation is always preferred over this approach.

Serializability

The strongest isolation level that guarantees that even though transactions may execute in parallel, the end result is the same as if they had executed one at a time, serially. which the database prevents all possible race conditions.

We can implement serializability in three different ways

- Actual/True Serial Execution

- Two Phase Locking (2PL)

- Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI)

Actual Serial Execution (one thread)

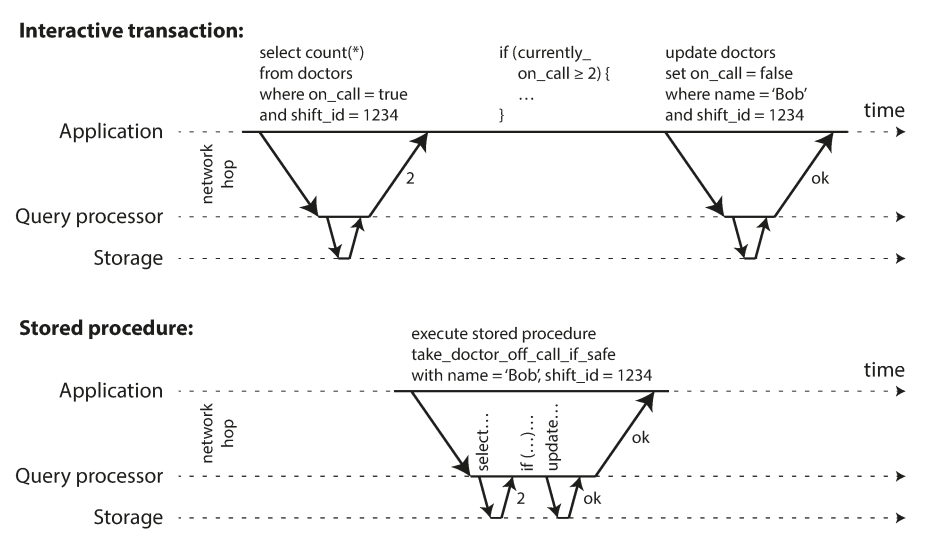

The easiest is actual serial execution, which to actually execute only one transaction at a time on a single thread. This approach wasn’t feasible until recently, as RAM become more cheaper, and database designers realized OLTP transactions usually makes a small number of reads and writes (in contrast with log-running analytical queries that should use snapshot isolation). Single thread execution can sometimes perform better than concurrent systems, however, the throughput is limited to single CPU.

To enhance the performance of serial executions, the application must submit the entire transaction code ahead of time as a stored procedure, which makes the performance reasonable, especially for databases with general-purpose programming languages. Partitioning can still be used with serial executions, especially when most transactions only uses one partition.

Pros and cons of stored procedures

- Each database vendor has its own language for stored procedures (Oracle has PL/ SQL, SQL Server has T-SQL, PostgreSQL has PL/pgSQL, etc.). These languages haven’t kept up with developments in general-purpose programming languages.

- Code running in a database is difficult to manage/debug: compared to an application server.

- A database is often much more performance-sensitive than an application server, because a single database instance is often shared by many application servers. A badly written stored procedure (e.g., using a lot of memory or CPU time) in a database can cause much more trouble than equivalent badly written code in an application server.

However, those issues can be overcome. Modern implementations of stored procedures have abandoned PL/SQL and use existing general-purpose programming languages instead: VoltDB uses Java or Groovy, Datomic uses Java or Clojure, and Redis uses Lua.

VoltDB also uses stored procedures for replication: instead of copying a transaction’s writes from one node to another, it executes the same stored procedure on each rep‐ lica. VoltDB therefore requires that stored procedures are deterministic (when run on different nodes, they must produce the same result). If a transaction needs to use the current date and time, for example, it must do so through special deterministic APIs.

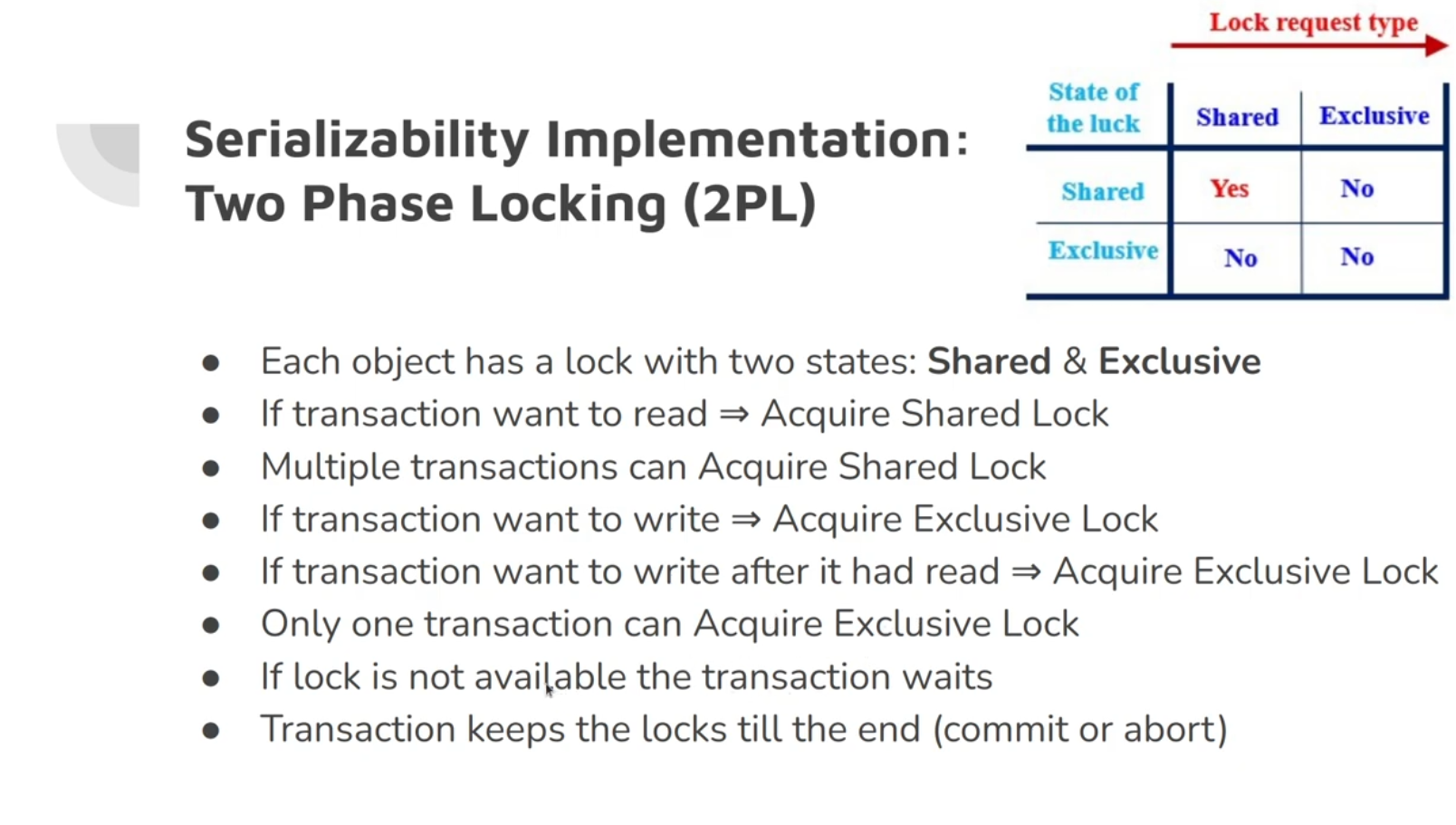

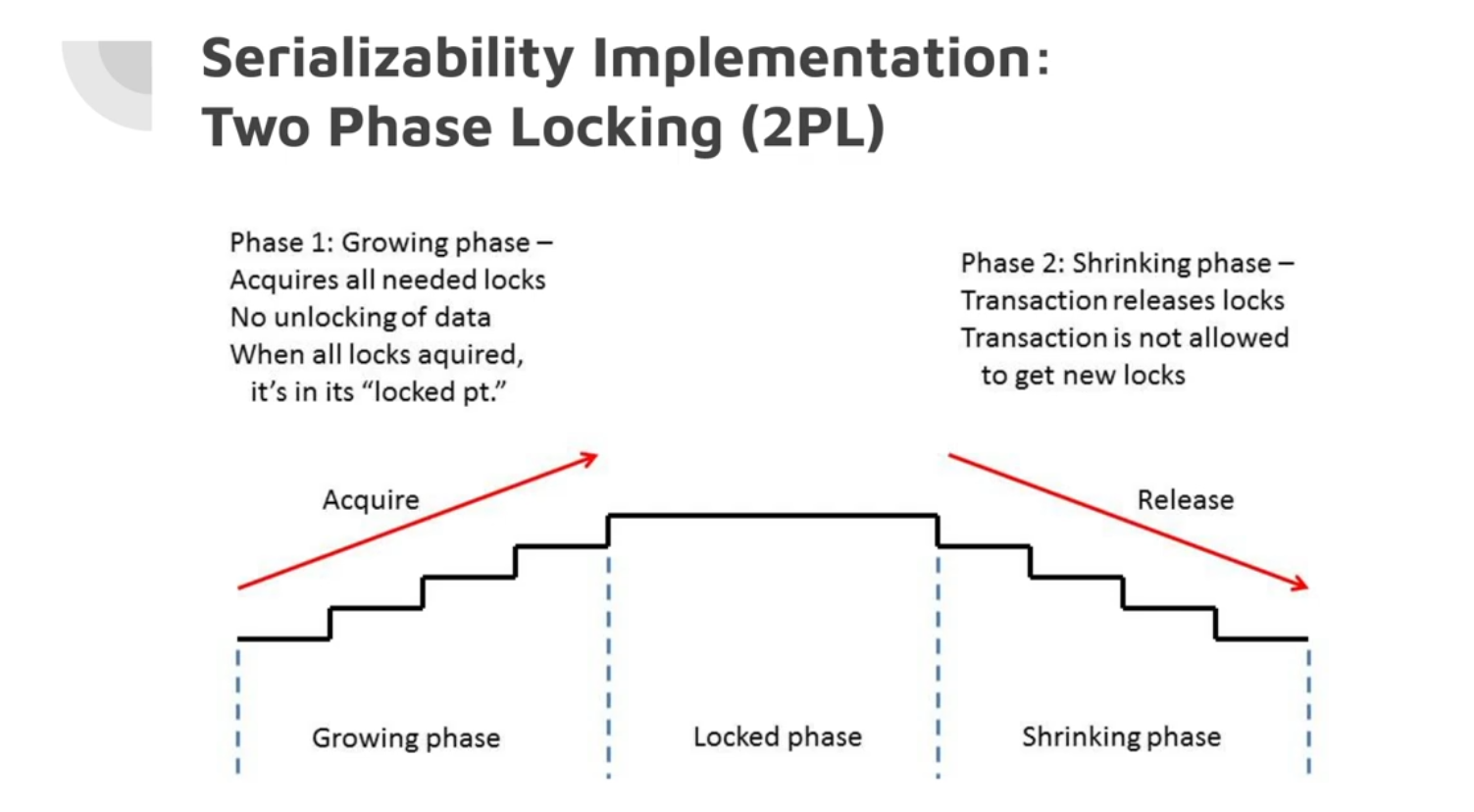

Two-Phase Locking (2PL)

Two Phase Locking is similar to dirty writes, but with more stronger requirements on the lock.

Also called pessimistic concurrency control mechanism: it is based on the principle that if anything might possibly go wrong (as indicated by a lock held by another transaction), it’s better to wait until the situation is safe again before doing anything.

If A has read an object and B wants to write to that object

-

B must wait until A commits or aborts

- B can’t change the object unexpectedly behind A’s back

If A has written an object and Transaction B wants to read it

-

B must wait until A commits or aborts

- This prevents reading an old version of the object

So writers block both other writers and readers, and vice versa. 2PL is used by the serializable isolation level in MySQL (InnoDB) and SQL Server.

Two modes of locks are provided, shared lock for readers, and exclusive lock for writes. Deadlocks might result from multiple transaction holding locks, then the database automatically detects deadlocks and aborts one of the transactions.

The big downside of two-phase locking is the performance, which is much worse compared to weak isolation, also it can have unstable latencies, and can be very slow at high percentiles due to the overhead of acquiring and releasing all those lock.

Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI)

This algorithm have the best performance to achieve serializability compared to previous algorithms and adds small performance penalty to Snapshot isolation. It fairly new: it was first described in 2008.

SSI is optimistic concurrency control which instead of blocking if something potentially dangerous happens, transactions continue anyway, in the hope that everything will turn out all right. When a transaction wants to commit, the database checks whether anything bad happened will aborted or retried.

This is the main difference compared to earlier optimistic concurrency control techniques. On top of snapshot isolation, SSI adds an algorithm for detecting serialization conflicts among writes and determining which transactions to abort.