Designing Data Intensive Applications Notes: Ch.12 The Future of Data Systems

Mohamed Kassem | November 04, 2023

Continuing our series for “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” book.

In this article, we will walkthrough the second chapter of this book Chapter.12 The Future of Data Systems.

Table Of Content (TOC)

Data Integration

The most appropriate choice of software tool also depends on the circumstan‐ ces. Every piece of software, even a so-called “general-purpose” database, is designed for a particular usage pattern.

You need to know how figure out the mapping between the software products and the circumstances in which they are a good fit.

Combining Specialized Tools by Deriving Data

For example, it is common to need to integrate an OLTP database with a full-text search index in order to handle queries for arbitrary keywords. Although some databases (such as PostgreSQL) include a full-text indexing feature, which can be suffi‐ cient for simple applications.

As the number of different representations of the data increases, the integration problem becomes harder. Besides the database and the search index, perhaps you need to keep copies of the data in analytics systems (data warehouses, or batch and stream processing systems); maintain caches or denormalized versions of objects that were derived from the original data; pass the data through machine learning, classification, ranking, or recommendation systems; or send notifications based on changes to the data.

Distributed transactions decide on an ordering of writes by using locks for mutual exclusion (Two-Phase Locking (2PL) but this always comes with some limitations and overheads (like XA has poor fault tolerance and performance), while CDC and event sourcing use a log for ordering. Distributed transactions use atomic commit to ensure that changes take effect exactly once, while log-based systems are often based on deterministic retry and idempotence.

In the absence of widespread support for a good distributed transaction protocol, I believe that log-based derived data is the most promising approach for integrating different data systems. However, guarantees such as reading your own writes are useful.

Batch and Stream Processing

Both batch processing and streaming processing has a quite strong functional flavor which is good for fault tolerance, and for reasoning about the dataflows inside an organization.it is helpful to think in terms of data pipelines that derive one thing from another, pushing state changes in one system through functional application code and applying the effects to derived systems.

The outputs of batch and stream processes are derived datasets such as search indexes, materialized views, recommendations to show to users, aggregate metrics, and so on.

Spark performs stream processing on top of a batch processing engine by breaking the stream into microbatches, whereas Apache Flink performs batch processing on top of a stream processing engine.

Derived views allow gradual evolution, which means we can maintain two (old and new) schemas side by side independently. The beauty of this is that we always have a working system to go back to.

Some systems which need a quickly approximated data through stream processing, as well as correct and reliable version of the data later through batch processing, usually use lambda architecture, which records incoming data as immutable events to an always-growing dataset, and runs both systems in parallel, where each uses a derived view. The only down side is the operational complexity of debugging and maintaining two different systems.

In the lambda approach, the stream processor consumes the events and quickly pro‐ duces an approximate update to the view; the batch processor later consumes the same set of events and produces a corrected version of the derived view.

Unbundling Databases

So far there are many various features provided by databases and how they work, including:

- Secondary indexes, which allow you to efficiently search for records based on the value of a field

- Materialized views, which are a kind of precomputed cache of query results

- Replication logs, which keep copies of the data on other nodes up to date

- Full-text search indexes, which allow keyword search in text

Database is consisted of different interacting components that we usually take for granted to work synchronously to achieve the desired storage role. This traditional synchronous actions require distributed transactions with all its overheads, so an asynchronous event-log (with Idempotence) might be a much more robust and practical approach, which leads us to the concept of unbundling the database.

Unbundling the database means building systems that abstractly acts like a database, but it in fact consists of a loosely coupled components. This has the advantages of making the system more robust to outages or performance degradation of individual components.

The goal of unbundling is to allow to combine several different databases in order to achieve good performance for much wider range of workloads that no single piece of software can satisfy them all.

Designing Applications Around Dataflow

deployment and cluster management tools such as Mesos, YARN, Docker, Kubernetes, and others are designed specifically for the purpose of running application code. By focusing on doing one thing well, they are able to do it much better than a database that provides execution of user-defined functions as one of its many features.

It might make sense to have some parts of a system that specialize in durable data storage, and other parts that specialize in running application code. The two can interact while still remaining independent.

Most web applications today are deployed as stateless services, in which any user request can be routed to any application server, and the server forgets everything about the request once it has sent the response. The trend has been to keep stateless application logic separate from state management (databases): not putting application logic in the database and not putting persistent state in the application. As people in the functional programming community like to joke, “We believe in the separation of Church and state”

The advantage of such a service-oriented architecture over a single monolithic application is primarily organizational scalability through loose coupling: different teams can work on different services, which reduces coordination effort between teams (as long as the services can be deployed and updated independently).

The difference between dataflow systems compared to microservices is that it has a one-directional, asynchronous communication mechanism, rather than synchronous request/response interaction, so instead of RPC we have a stream join between events.

dataflow systems can also achieve better performance. For example, say a customer is purchasing an item that is priced in one currency but paid for in another currency. In order to perform the currency conversion, you need to know the current exchange rate. This operation could be implemented in two ways:

- In the microservices approach, the code that processes the purchase would probably query an exchange-rate service or database in order to obtain the current rate for a particular currency

- .In the dataflow approach, the code that processes purchases would subscribe to a stream of exchange rate updates ahead of time, and record the current rate in a local database whenever it changes. When it comes to processing the purchase, it only needs to query the local database.

Not only is the dataflow approach faster, but it is also more robust to the failure of another service. The fastest and most reliable network request is no network request at all! Instead of RPC, we now have a stream join between purchase events and exchange rate update events.

Observing Derived State

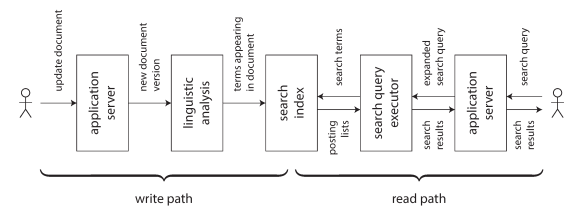

The following diagram shows an example of updating a search index when write and read.

HTTP-based feed subscription protocols like RSS are really just a basic form of polling.

More recent protocols have moved beyond the basic request/response pattern of HTTP: server-sent events (the EventSource API) and WebSockets provide communication channels by which a web browser can keep an open TCP connection to a server, and the server can actively push messages to the browser as long as it remains connected. This provides an opportunity for the server to actively inform the enduser client about any changes to the state it has stored locally, reducing the staleness of the client-side state

Recent tools for developing stateful clients and user interfaces, such as the Elm language and Facebook’s toolchain of React, Flux, and Redux, already manage internal client-side state by subscribing to a stream of events representing user input or responses from a server, structured similarly to event sourcing. Some applications, such as instant messaging and online games, already have such a “real-time” architecture

The ideas of stream processing and messaging and not restricted to datacenters, but we can extend them all the way to the end-user devices.

Aiming for Correctness

Transactions have been the choice for building correct applications for more than four decades by now, and while in some areas they have been completely abandoned for their overheads, they are not going away, but also correctness can be achieved in the context of dataflow.

Data systems that provide strong safety properties (eg. serializable transactions) are not guaranteed to be free from data loss or corruption. However, it would be easier to recover from such mistakes by preventing faulty code from destroying good (immutable) data. One of the most effective approaches to achieve this is to make all operations idempotent.

Duplicate suppression can be happened TCP connection for a client’s connection to a database and it is currently executing the following transaction

# This transaction is non-idempotent

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance + 11.00 WHERE account_id = 1234;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance - 11.00 WHERE account_id = 4321;

COMMIT;In many databases, a transaction is tied to a client connection (if the client sends several queries, the database knows that they belong to the same transaction because they are sent on the same TCP connection). If the client suffers a network interruption and connection timeout after sending the COMMIT, but before hearing back from the database server, it does not know whether the transaction has been committed or aborted.

Two-phase commits are not sufficient to ensure that the transaction will be executed once, so to make an operation idempotent, we need to consider end-to-end flow of the whole operation. For example, you could generate a unique identifier for an operation (such as a UUID) and include it as a hidden form field in the client application, or calculate a hash of all the relevant form fields to derive the operation ID. If the web browser submits the POST request twice, the two requests will have the same operation ID.

ALTER TABLE requests ADD UNIQUE (request_id); # if the request has the same request_id, the insert will fail

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

INSERT INTO requests

(request_id, from_account, to_account, amount)

VALUES('0286FDB8-D7E1-423F-B40B-792B3608036C', 4321, 1234, 11.00);

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance + 11.00 WHERE account_id = 1234;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance - 11.00 WHERE account_id = 4321;

COMMIT;Enforcing Constraints

The most common way of achieving consensus is by having a single leader node, but also the unbundled database approach with log-based messaging have a similar approach to enforce uniqueness constraint.

Traditionally, executing transactions across multiple partitions requires an atomic commit, but equivalent correctness can be achieved with partitioned logs as follows:

- The request is given a unique ID by the client, and atomically appended to the log partitioned based on its ID

- A stream processor reads the log for requests, and emits message(s) with the request ID to output streams

- Further processors consumes the output streams

This algorithm is basically the same as in “Implementing linearizable storage using total order broadcast”. It scales easily to a large request throughput by increasing the number of partitions, as each partition can be processed independently.

Timeliness and Integrity

Timeliness means ensuring that users observe the system in an up-to-date state. Integrity means absence of corruption; i.e., no data loss, and no contradictory or false data

Consistency conflates two different requirements, which are timeliness and integrity. Violation of timeliness is eventual consistency, whereas violation of integrity is perpetual consistency and can be catastrophic!

For example, on your credit card statement, it is not surprising if a transaction that you made within the last 24 hours does not yet appear—it is normal that these systems have a certain lag. We know that banks reconcile and settle transactions asynchronously, and timeliness is not very important here. However, it would be very bad if the statement balance was not equal to the sum of the transactions plus the previous statement balance (an error in the sums), or if a transaction was charged to you but not paid to the merchant (disappearing money). Such problems would be violations of the integrity of the system.

ACID transactions usually provide both timeliness (e.g., linearizability) and integrity (e.g., atomic commit) guarantees. Thus, if you approach application correctness from the point of view of ACID transactions, the distinction between timeliness and integrity is fairly inconsequential.

Event-based dataflow systems decouples timeliness and integrity, there is no guarantee of timeliness, but integrity can be achieved through:

- Representing the content of the atomic write operation as a single message, an approach that fits very well with event sourcing.

- Deriving all other state updates from the single message using deterministic derivation functions

- Passing a client-generated request ID through all these levels of processing, enabling end-to-end duplicate suppression

- Making messages immutable

Some applications do require integrity: you would not want to lose a reservation, or have money disappear due to mismatched credits and debits. But they don’t require timeliness on the enforcement of the constraint: if you have sold more items than you have in the warehouse, you can patch up the problem after the fact by apologizing.

In this context, serializable transactions are still useful as part of maintaining derived state, but they can be run at a small scope where they work well. Heterogeneous distributed transactions such as XA transactions are not required. Synchronous coordination can still be introduced in places where it is needed (for example, to enforce strict constraints before an operation from which recovery is not possible), but there is no need for everything to pay the cost of coordination if only a small part of an application needs it.

Trust, but Verify

It is always a good idea not to just blindly trust the guarantees given by a software, no matter how widely used it is, because bugs can always creep in. We should have a way of finding out (preferably automatically and continually) if the data has been corrupted so that we can fix it and track down the source of error. This is known as auditing.

Event-based systems can provide better auditability than transaction-based systems, as it gives a clear picture of why the mutations were performed. Also, a deterministic and well-defined dataflow makes it easier to debug and trace the execution of the system.

It would be better if we can check that the entire derived data pipeline is correct end-to-end, which can give us confidence about the correctness of any disks, networks, services, and algorithms along the path.

Having continuous end-to-end integrity checks gives you increased confidence about the correctness of your systems, which in turn allows you to move faster. Like automated testing, auditing increases the chances that bugs will be found quickly, and thus reduces the risk that a change to the system or a new storage technology will cause damage. If you are not afraid of making changes, you can much better evolve an application to meet changing requirements.

Tools for auditable data systems

It would be interesting to use cryptographic tools to prove the integrity of a system in a way that is robust to a wide range of hardware and software issues, and even potentially malicious actions. Cryptocurrencies, blockchains, and distributed ledger technologies such as Bitcoin, Ethereum, Ripple, Stellar, and various others have sprung up to explore this area.

Cryptographic auditing and integrity checking often relies on Merkle trees, which are trees of hashes that can be used to efficiently prove that a record appears in some dataset (and a few other things). Outside of the hype of cryptocurrencies, certificate transparency is a security technology that relies on Merkle trees to check the validity of TLS/SSL certificates.

Doing the Right Thing

Every system is built for a purpose which has both intended and unintended consequences. We are responsible to carefully consider those consequences.

A technology is not good or bad in itself—what matters is how it is used and how it affects people. This is true for a software system like a search engine in much the same way as it is for a weapon like a gun. I think it is not sufficient for software engineers to focus exclusively on the technology and ignore its consequences: the ethical responsibility is ours to bear also. Reasoning about ethics is difficult, but it is too important to ignore

Predictive Analytics

Predictive analytics systems which usually rely on machine learning can be very misleading. If there is a systematic bias in the input, the system will most likely learn and amplify that bias in the output.

Predictive analytics systems do not merely automate a human’s decision by using software to specify the rules for when to say yes or no; instead we leave the rules themselves to be inferred from the data.

Consequences such as feedback loops can be predicted by thinking about the entire system, including the people interacting with it – an approach known as systems thinking.

Privacy and Tracking

When a system only stores data that has been explicitly entered, then the system is performing a service for the user: The user is the customer.

Tracking the user serves not the individual but the needs of advertisers who are funding the service. This relationship is appropriately described as surveillance.

Privacy does not mean keeping everything secret, but having the freedom to choose which things to reveal to whom, what to make public, and what to keep secret.

When data is extracted from people through surveillance infrastructure, privacy rights are usually not eroded but rather transferred to the data collector.

Whether something is “undesirable” or “inappropriate” is down to human judgment; algorithms are oblivious to such notions unless we explicitly program them to respect human needs.

Surveillance has always existed, but it used to be expensive and manual. Trust relationships have always existed, but the are mostly governed by ethical, legal, and regulatory constraints.

Just as the Industrial Revolution had a dark side that needed to be managed, our transition to the information age has major problems that we must confront and solve.

As Bruce Schneier said, data is the pollution problem of the information age, and protecting privacy is the environmental challenge.