Designing Data Intensive Applications Notes: Ch.11 Stream Processing

Mohamed Kassem | November 04, 2023

Continuing our series for “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” book.

In this article, we will walkthrough the second chapter of this book Chapter.11 Stream Processing.

Table Of Content (TOC)

- Messaging System

- Partitioned Logs (Kafka)

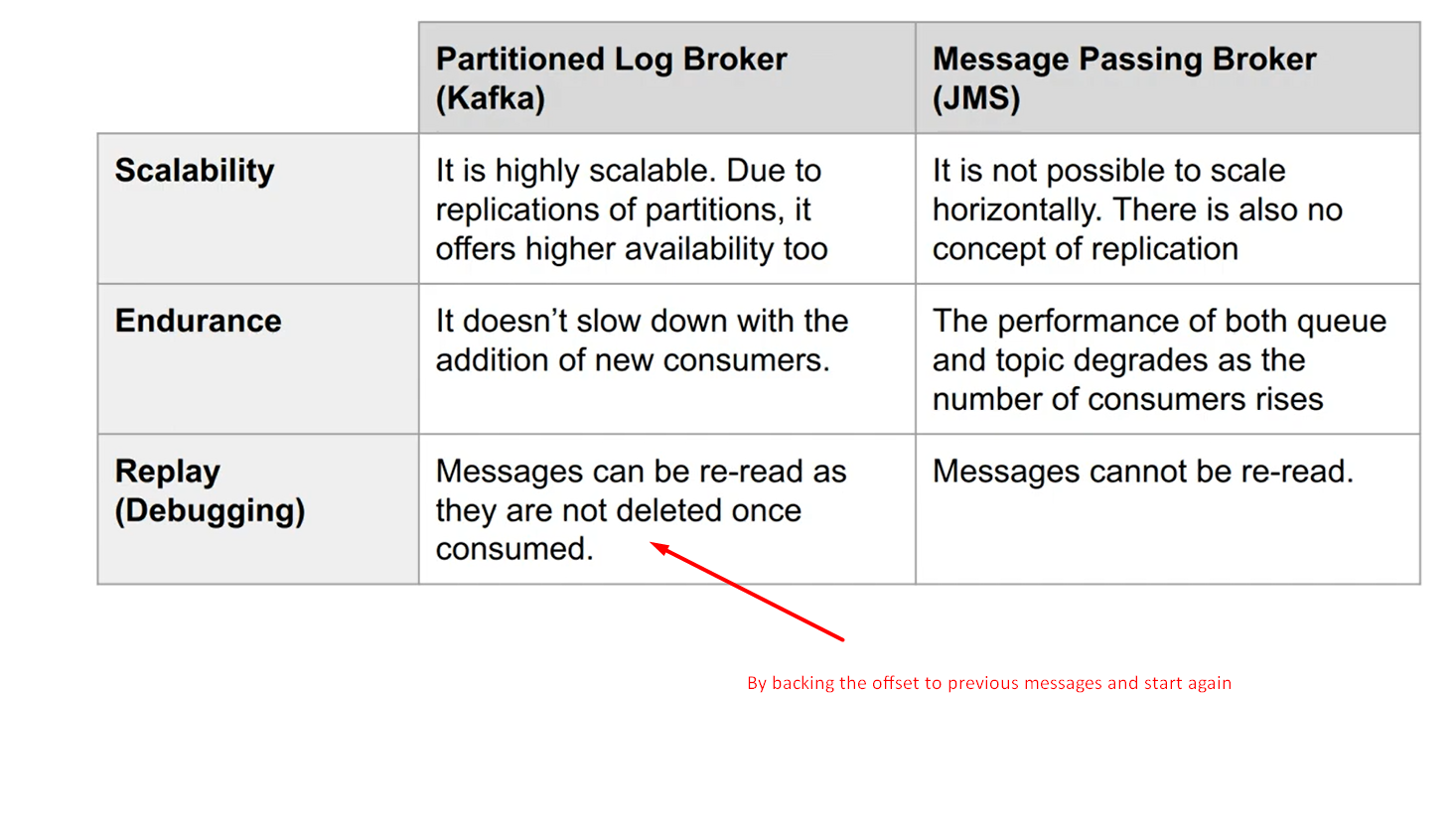

- Partitioned Log Broker vs Message Queue/Passing Broker

- Processing Streams

- Uses of Stream Processing

What is Steam?

Stream refers to data that is incrementally made available over time. So the dataset never ends and we need to process the data received up till now. On the other hand, in batch processing we know when the database has finished, we can start computation after that.

In streaming, the input is an event which immutable object containing the details of something that happened at some point in time. It may be encoded as a text string, or JSON, or perhaps in some binary form.

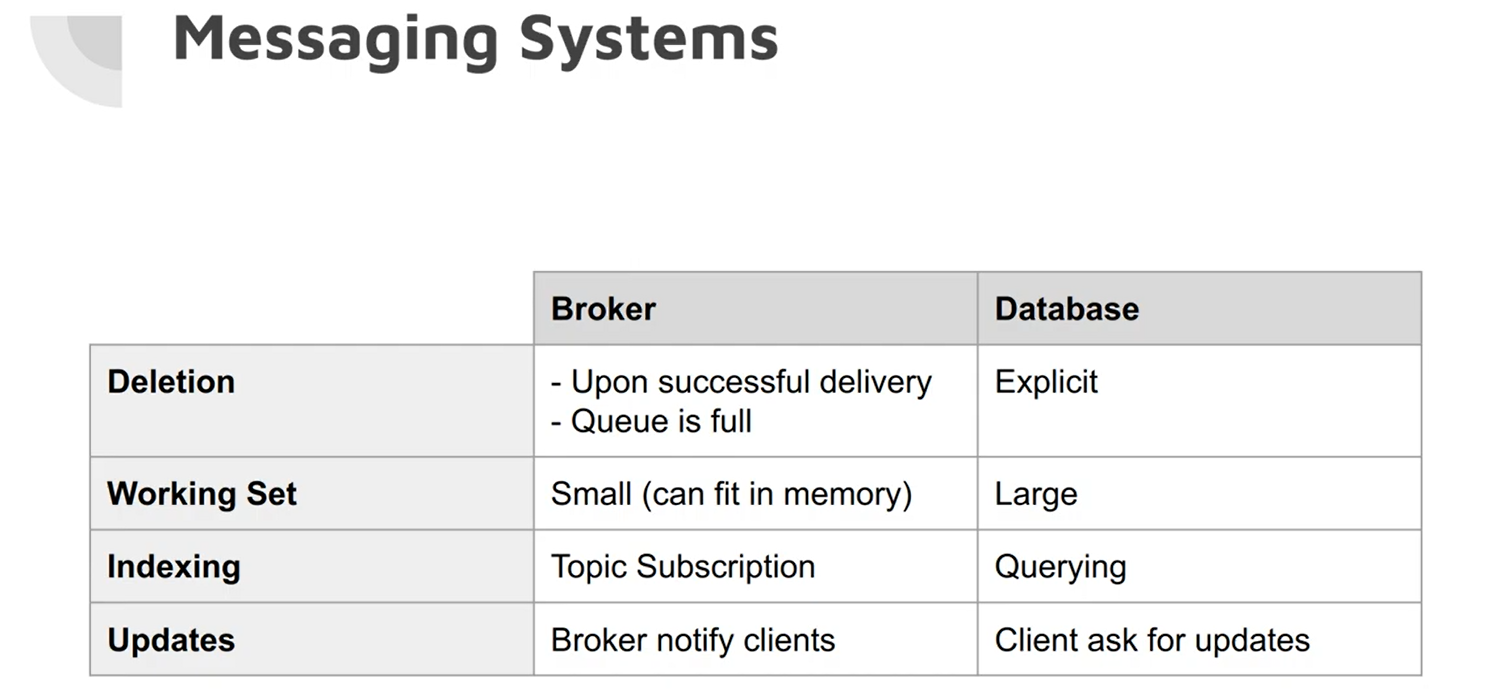

A database is sufficient to connect producers and consumers. However, continuous polling is expensive, so its better for consumers to be notified when new events appear, the behavior that usually requires specialized tools such as messaging systems.

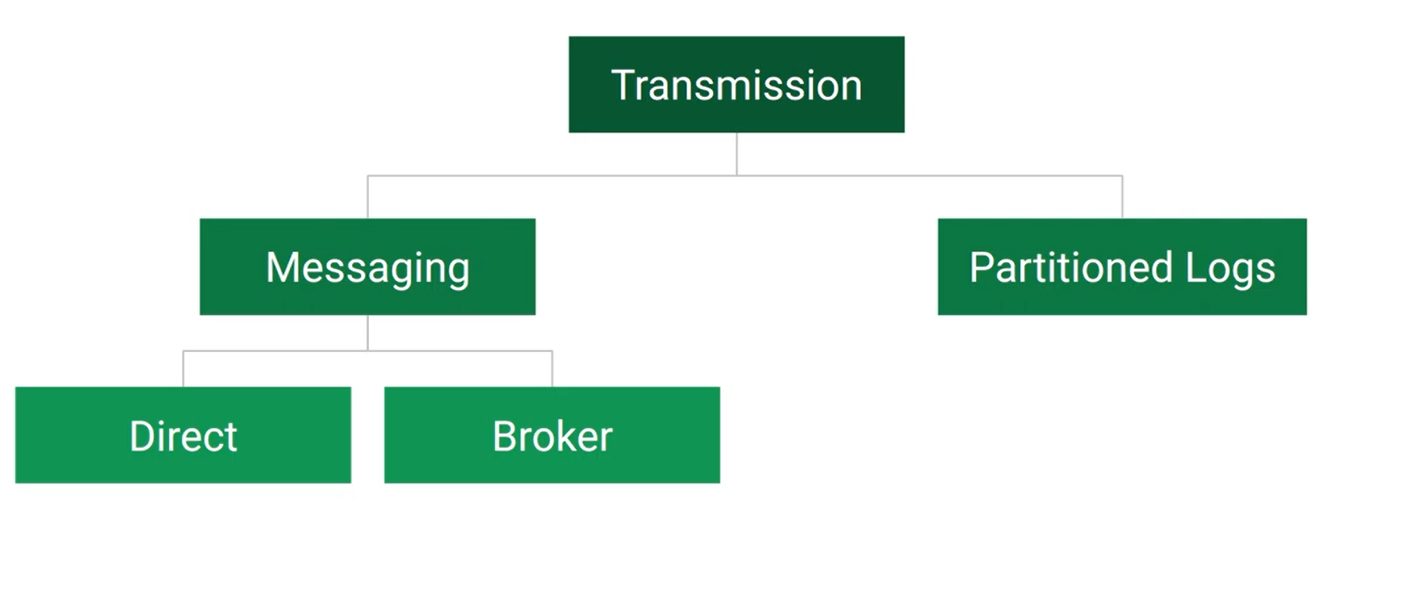

Messaging System

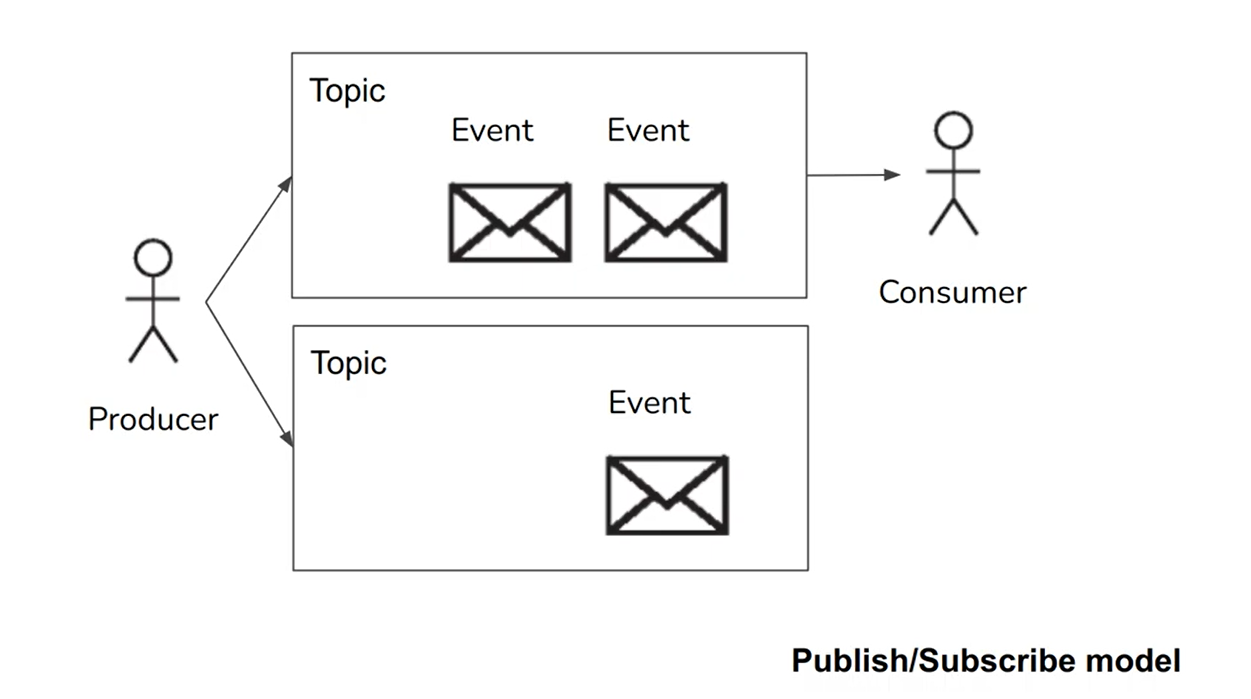

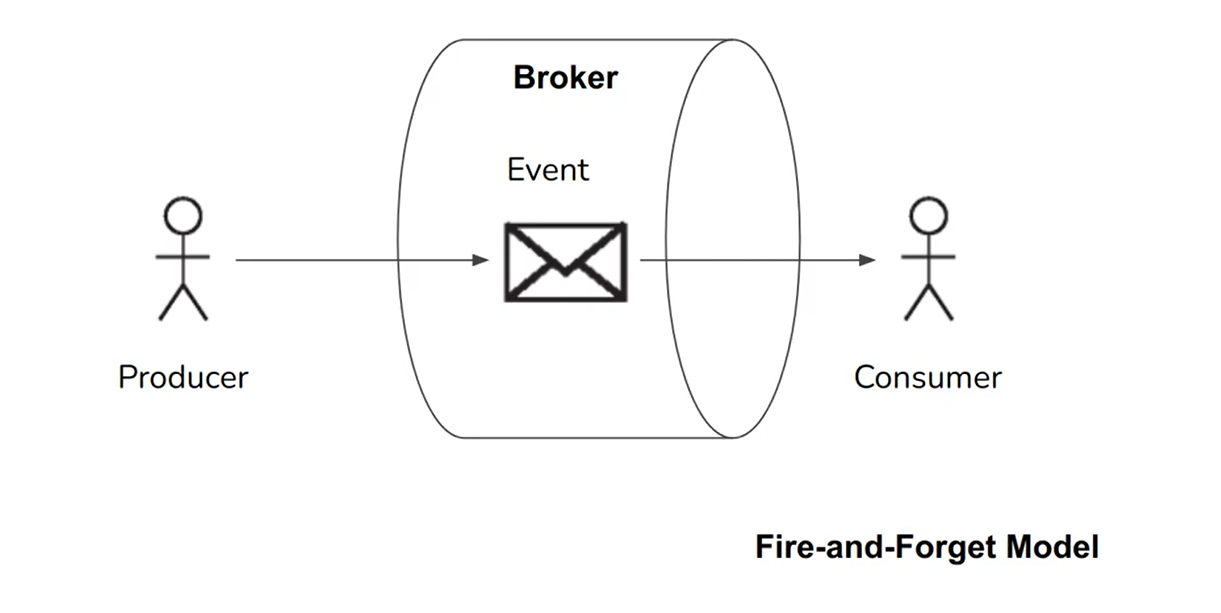

A common approach for notifying consumers about new events is to use Messaging systems: allows multiple producers nodes to send messages to the same topic and allows multiple consumer nodes to receive messages in a topic.

Within this publish/subscribe model, it might be helpful to ask the following two questions:

- What happens if the producers send messages faster than the consumers can process them? the system can drop messages, buffer messages in a queue, or apply backpressure (block producer to send new events).

- What happens if nodes crash or temporarily go offline—are any messages lost? it depends on the application, like if with sensor streaming which missing data point perhaps not important. And for durability, a combination of writing messages to disk and having replication might be used, but with a cost of lower throughput and higher latency.

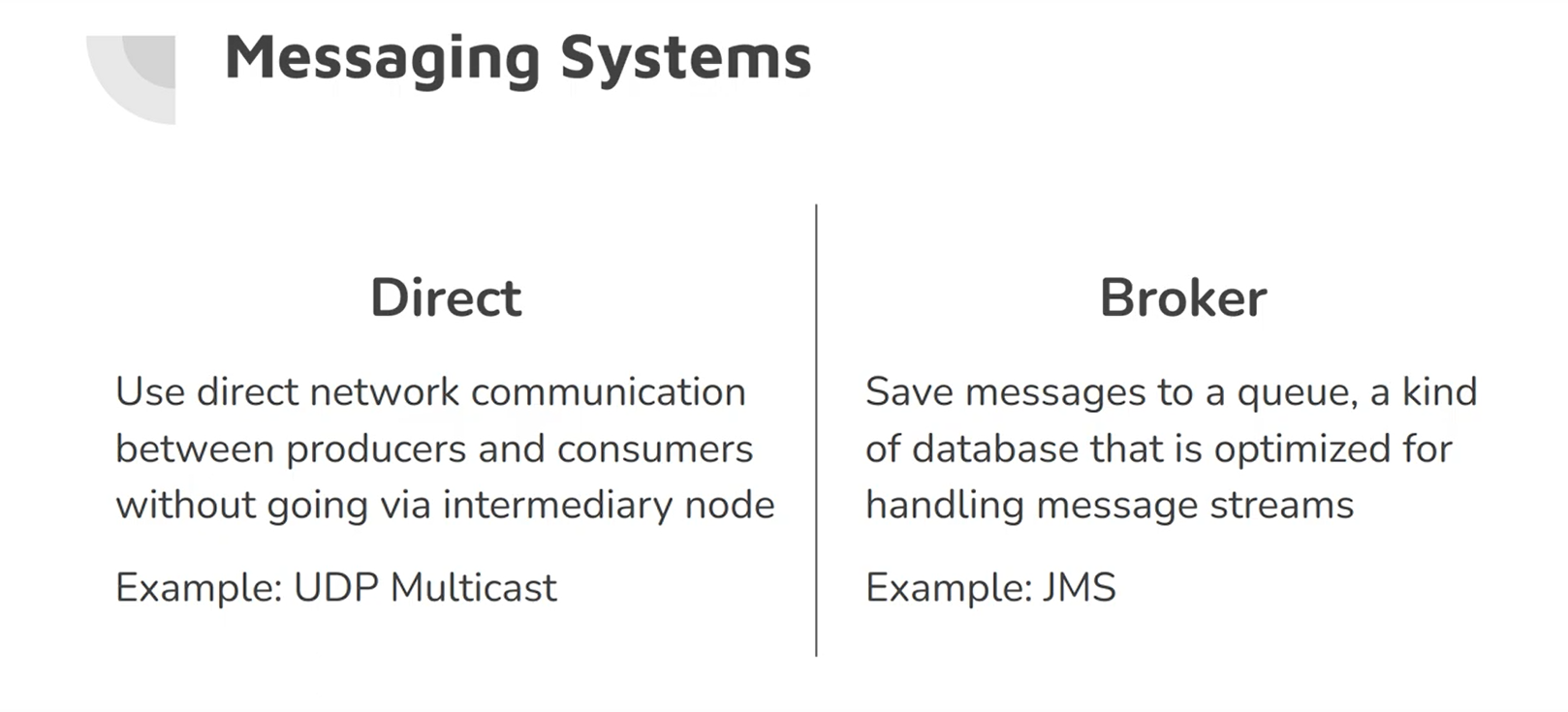

One option for a messaging system is direct network communication, such as UDP multi-cast, broker-less messaging libraries like ZeroMQ, or direct HTTP or RPC requests. However, their biggest drawback is that they require applications to be aware of loss possibility.

Another more widely used option is communication via a message broker or message queue, which acts as a server that both producers and consumers connect to, it automatically deletes a message after delivery, it supports some way of subscribing to a subset of topics, and it notifies clients when data changes. Consumers are generally asynchronous: when a producer sends a message, it normally only waits for the broker to confirm that it has buffered the message and does not wait for the message to be processed by consumers

This is the traditional view of message brokers, which is encapsulated in standards like JMS and AMQP and implemented in software like RabbitMQ, ActiveMQ, HornetQ, Qpid, TIBCO Enterprise Message Service, IBM MQ, Azure Service Bus, and Google Cloud Pub/Sub.

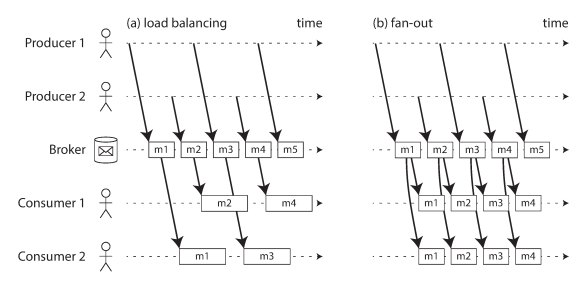

Message Broker can decide to distribute the event load among consumers (Load balancing), or deliver all messages to all consumers (Fan-out), or a combination of both.

Acknowledgments and redelivery

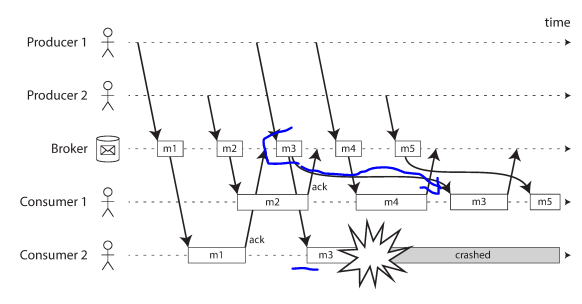

Message brokers use acknowledgments: a client must explicitly tell the broker when it has finished processing a message so that the broker can remove it from the queue. If the connection to a client is closed or times out without the broker receiving an acknowledgment, it assumes that the message was not processed, and therefore it delivers the message again to another consumer.

In load balancing approach, The following example, consumer 2 crashes while processing m3, so it is redelivered to consumer 1 at a later time.

But this leads to inconsistency with the order that were sent by producer 1. Message broker tries to preserve the order of messages and use a separate queue per consumer to solve this issue.

Partitioned Logs (Kafka)

Log-based message brokers is simply an append-only sequence of records on disk. A producer sends a message by appending it to the end of the log, and a consumer receives messages by reading the log sequentially. If a consumer reaches the end of the log, it waits for a notification that a new message has been appended. The Unix tool tail -f, which watches a file for data being appended, essentially works like this.

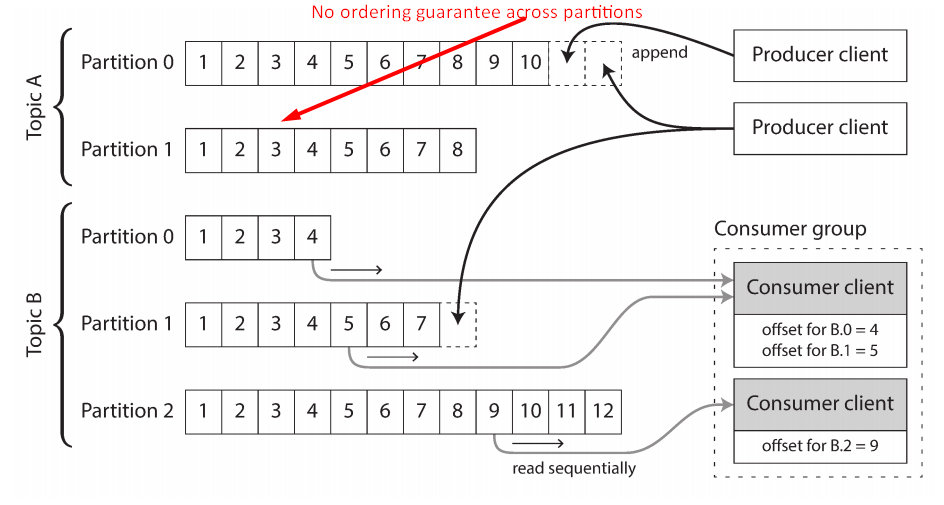

For scaling out, the log is partitioned on different machines, making each partition is independently for other partitions. A topic is defined to group some partitions. Each consumer has a read offset per partition and be grouped also.

Apache Kafka, Amazon Kinesis Streams, and Twitter’s DistributedLog are log-based message brokers that work like this. Google Cloud Pub/Sub is architecturally similar but exposes a JMS-style API rather than a log abstraction

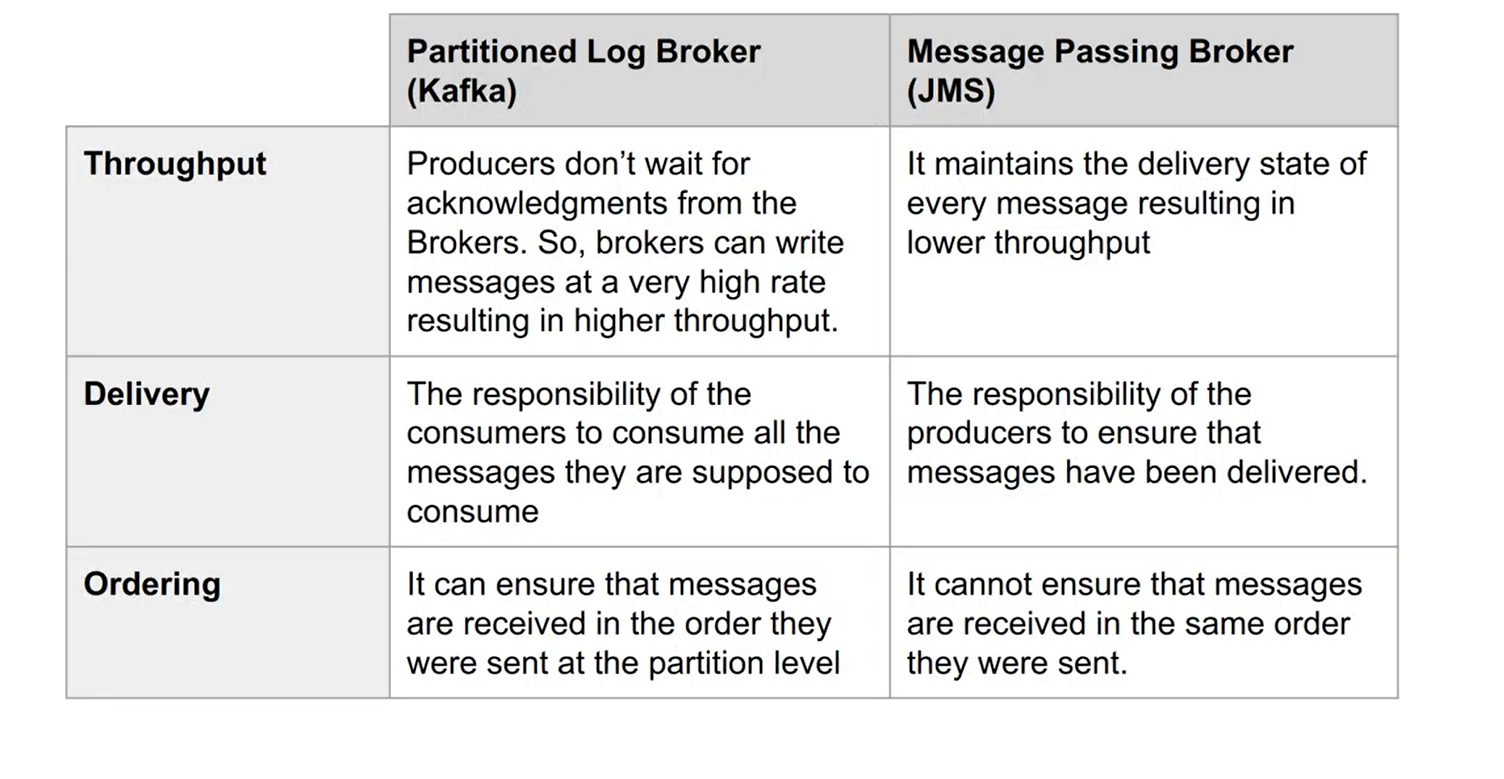

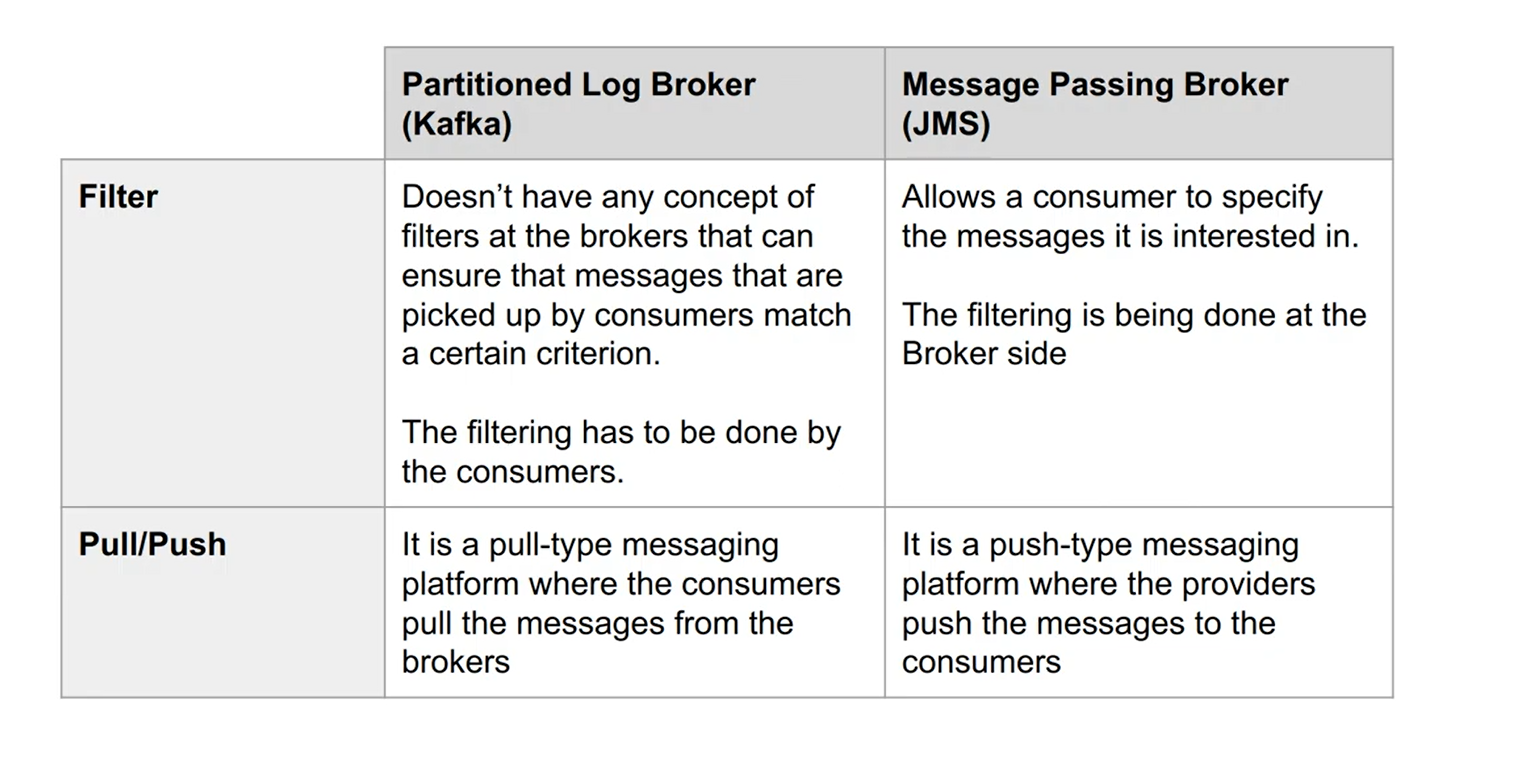

Partitioned Log Broker vs Message Queue/Passing Broker

Databases and Streams

A database can be represented as a stream, where an event can be something that was written to a database, it can be captured, stored, and processed. This representation opens up powerful opportunities for integrating systems.

Keeping systems in Sync

Most nontrivial applications need to combine several different technologies in order to satisfy their requirements: for example, using an OLTP database to serve user requests, a cache to speed up common requests, a full-text index to handle search queries, and a data warehouse for analytics. Each of these has its own copy of the data, stored in its own representation that is optimized for its own purposes.

If an item is updated in the database, it also needs to be updated in the cache, search indexes, and data warehouse (By ETL process and full copy of the database). If periodic full database dumps are too slow, an alternative that is sometimes used is dual writes, in which the application code explicitly writes to each of the systems when data changes: for example, first writing to the database, then updating the search index, then invalidating the cache entries (or even performing those writes concurrently).

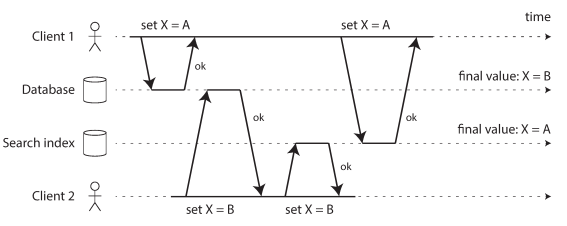

The problems with dual writes:

-

Race condition can happened

In the database, X is first set to A and then to B, while at the search index the writes arrive in the opposite order.

- There is no Atomic Commit

A better approach for data sync is change data capture (CDC).

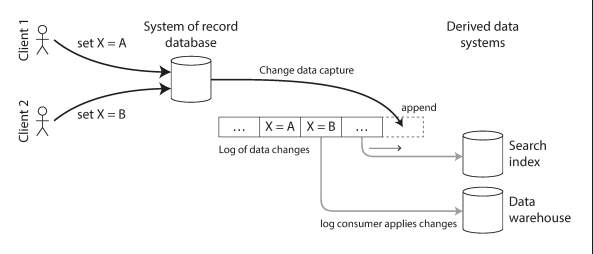

Change Data Capture (CDC)

The process of observing all data changes written to a database and extracting them in a form in which they can be replicated to other systems (eg. search index).It allows the database to act as a leader to other followers.

The following diagram shows, Taking data in the order it was written to one database, and applying the changes to other systems in the same order.

A log-based message broker is well suited for transporting the change events from the source database, since it preserves the ordering of messages.

LinkedIn’s Databus, Facebook’s Wormhole, and Yahoo!’s Sherpa use this idea at large scale. Bottled Water implements CDC for PostgreSQL using an API that decodes the write-ahead log, Maxwell and Debezium do something similar for MySQL by parsing the binlog, Mongoriver reads the MongoDB oplog, and GoldenGate provides similar facilities for Oracle.

It is usually implemented by parsing the replication log of the database, which relies on taking consistent snapshots regularly and log compaction to avoid running out of space. Which is periodically looks for log records with the same key, throws away any duplicates, and keeps only the most recent update for each key, an update with a special null value (a tombstone) indicates that a key was deleted. This compaction and merging process runs in the background.

Now, whenever you want to rebuild a derived data system such as a search index, you can start a new consumer from offset 0 of the log-compacted topic, and sequentially scan over all messages in the log. This log compaction feature is supported by Apache Kafka.

Kafka Connect is an effort to integrate change data capture tools for a wide range of database systems with Kafka.

Event Sourcing

Like CDC, event sourcing involves storing all changes to the application state as a log of change events. The big differences are:

- In CDC, the application uses the database in a mutable way, updating and deleting records at will. The log of changes is extracted from the database at a low level (e.g., by parsing the replication log)

- In event sourcing, the application logic is explicitly built on the basis of immutable events that are written to an event log. In this case, the event store is append-only, and updates or deletes are discouraged or prohibited

Event sourcing is a powerful technique for data modeling: from an application point of view it is more meaningful to record the user’s actions as immutable events, rather than recording the effect of those actions on a mutable database. Event sourcing makes it easier to evolve applications over time, helps with debugging by making it easier to understand after the fact why something happened, and guards against application bugs.

For example, storing the event “student cancelled their course enrollment” clearly expresses the intent of a single action in a neutral fashion, whereas the side effects “one entry was deleted from the enrollments table, and one cancellation reason was added to the student feedback table” embed a lot of assumptions about the way the data is later going to be used. If a new application feature is introduced—for example, “the place is offered to the next person on the waiting list”—the event sourcing approach allows that new side effect to easily be chained off the existing event.

Applications that use event sourcing need to take the log of events and transform it into application state that is suitable for showing to a user. This transformation can use arbitrary logic, but it should be deterministic so that you can run it again and derive the same application state from the event log.

The biggest downside of CDC and event sourcing is that the consumers of the event log are usually asynchronous, which might lead to failure in reading your own writes. One solution is perform updates on read view synchronously, but a better approach might be to implement linearizable storage using total order broadcast. However, if the event log and application state are partitioned in the same way, then a single-threaded log consumer needs no concurrency control for writes.

The limitations of immutability is that immutable history may grow very large, causing the system to perform poorly. Also, for administrative reasons, data must be completely deleted in some cases, which is surprisingly hard.

Processing Streams

what you can do with the stream once you have it— namely, you can process it. Broadly, there are three options:

- Write it to a database, cache, search index, .. etc

- Preview at an application for the user like notifications, real-time dashboard

- Pipeline to another stream

Uses of Stream Processing

- Fraud detection systems need to determine if the usage patterns of credit card has unexpectedly changes, and block the card if it is likely to have bean stolen.

- Trading systems need to examine price changes in a financial market and execute trades according to specified rules.

- Manufacturing systems need to monitor the status of machines in a factory, and quickly identify the problem if there is a malfunction.

- Military and intelligence systems need to track the activities of a potential aggressor, and raise the alarm if there are signs of an attack.

Stream Operations

These are the operations that can be applied to stream.

Complex Event Processing (CEP)

- Allow you to specify rules to search for certain patterns of events in a stream.

- CEP systems often use a high-level declarative query language like SQL, or a GUI, to describe the patterns of events that should/need be detected

- When a match is found, the engine emits a complex event with details of the event pattern that was detected.

Stream Analytics

Finding aggregations and statistical metrics over a large number of events over window/period of time:

- Measuring the rate of some type of event (how often it occurs per time interval)

- Calculating the rolling average of a value over some time period

- Comparing current statistics to previous time intervals (e.g. to detect trends or alert on metrics that are unusually high or low compared to the same time last week)

Many open source distributed stream processing frameworks are designed with analytics in mind: for example, Apache Storm, Spark Streaming, Flink, Concord, Samza, and Kafka Streams. Hosted services include Google Cloud Dataflow and Azure Stream Analytics.

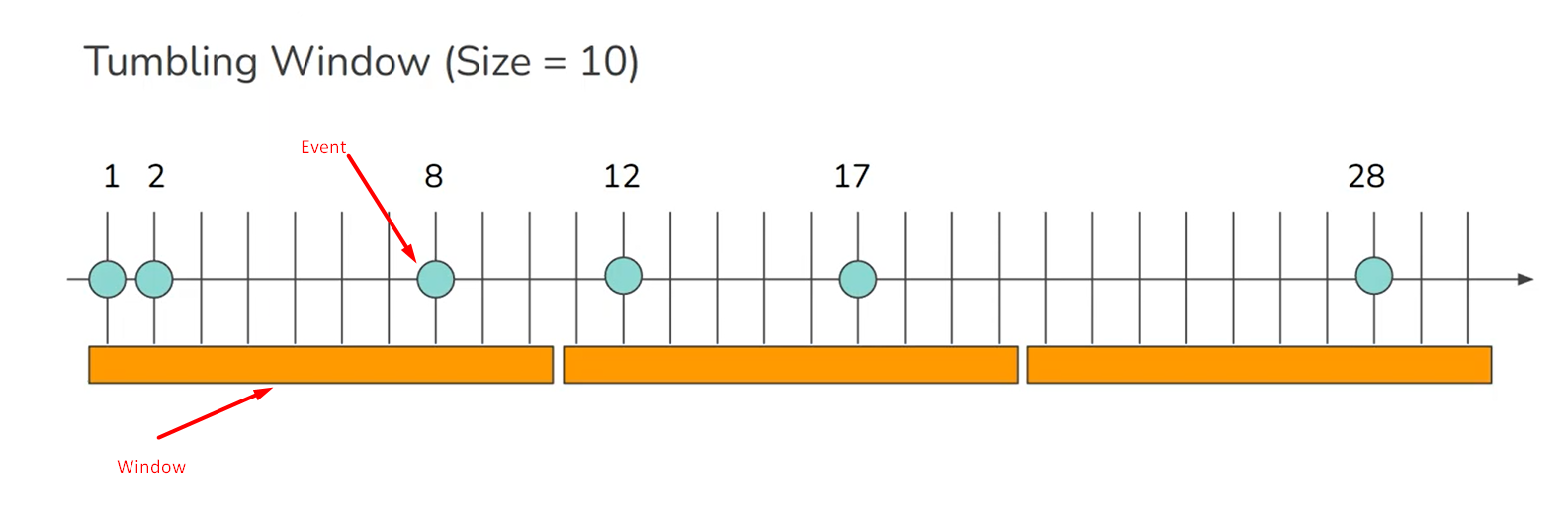

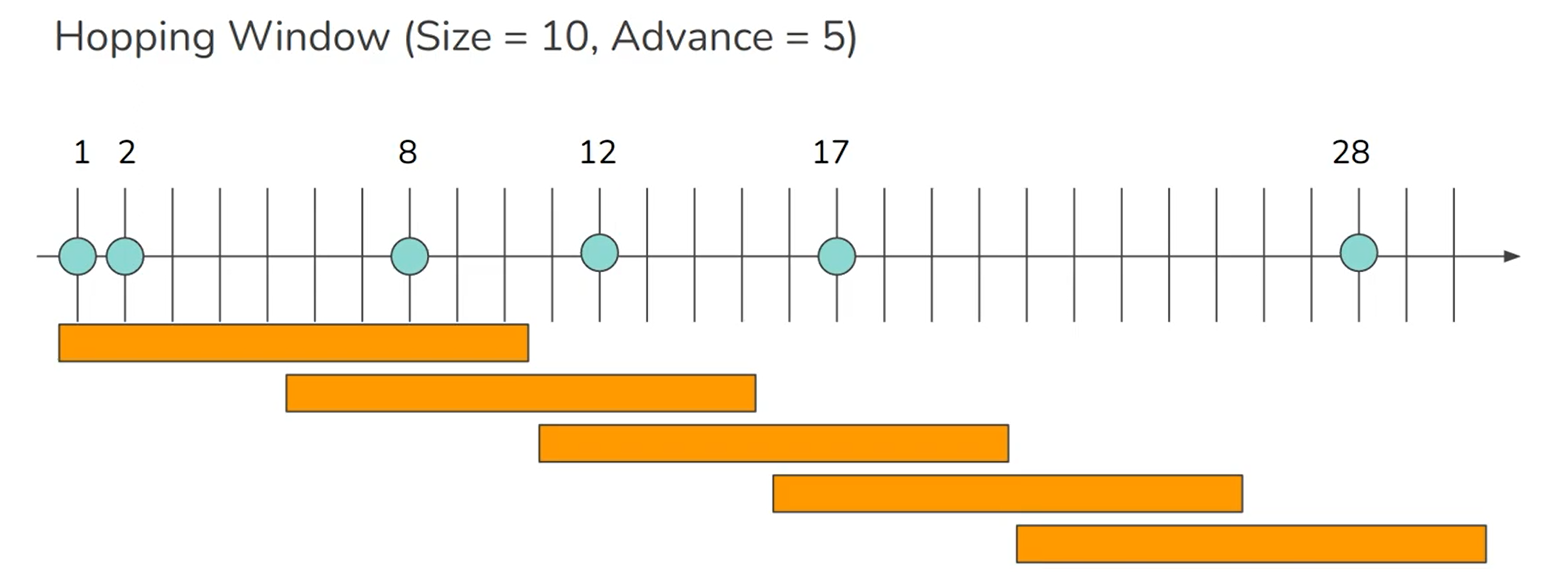

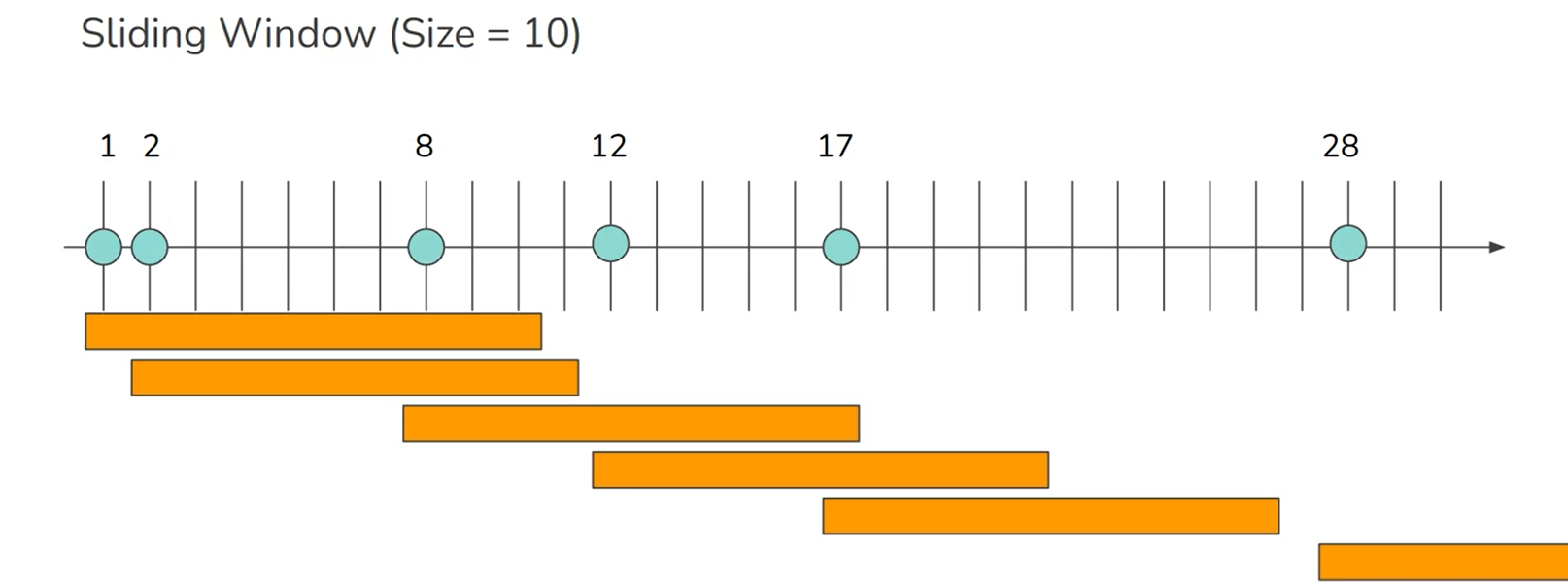

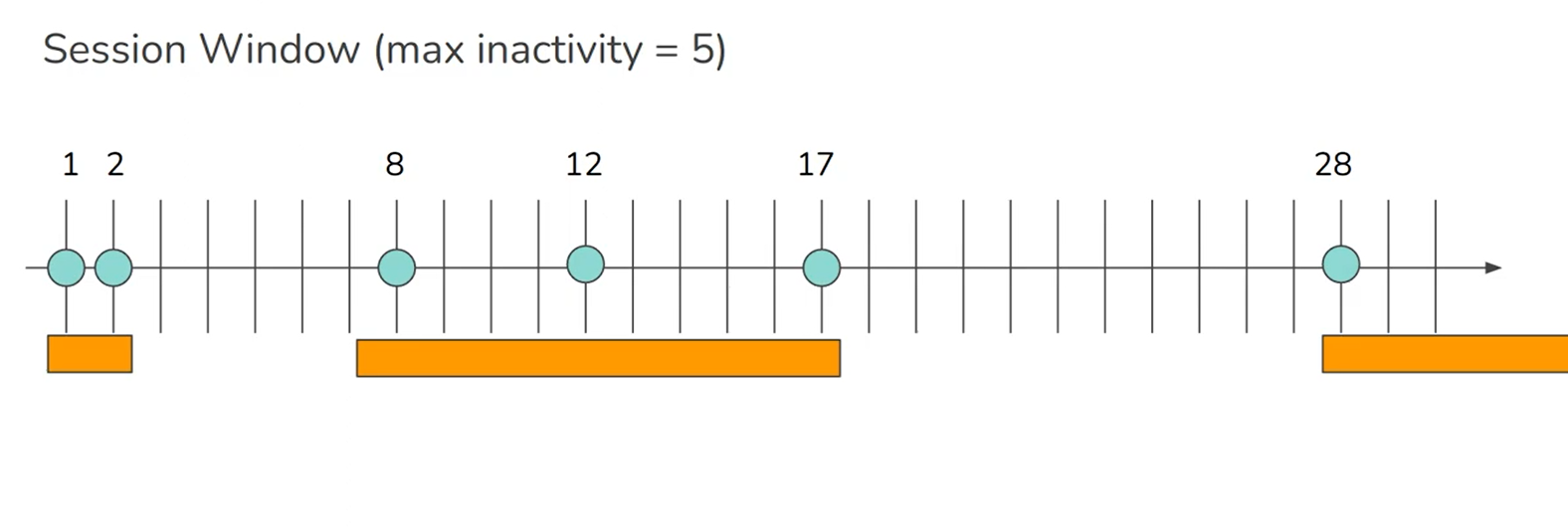

Types of windows

-

Tumbling window: Fixed length, for example, if you have a 1-minute tumbling window, all the events with timestamps between 10:03:00 and 10:03:59 are grouped into one window.

-

Hopping window: also has a fixed length, but allows windows to overlap in order to provide some smoothing. For example, a 5-minute window with a hop size of 1 minute would contain the events between 10:03:00 and 10:07:59, then the next window would cover events between 10:04:00 and 10:08:59, and so on.

-

Sliding window: Fixed length but by event occurred, make a new window

-

Session window: defined by grouping together all events for the same user that occur closely together in time, and the window ends when the user has been inactive for some time

When to use each of window type?

- Tumbling ⇒ Event appears at only one window.

- Hopping ⇒ Scheduled based

- Sliding ⇒ Event based

- Session ⇒ Activity based

Search Streams

Besides CEP, which allows searching for patterns consisting of multiple events, there is also sometimes a need to search for individual events based on complex criteria, such as full-text search queries.

Formulating a search query in advance, and then continually matching the stream of news items against this query.

Similar to search engines first index the data and then run queries over the index. By contrast, searching a stream turns the processing on its head: the queries are stored and indexed, and the events run past the queries.

Join Streams

Same as batch processing, stream processing needs to do joins, either by joining a stream to another stream , or a stream to a table, or two tables. The three types of joins requires the stream processor to maintain some state based on the join input, and a query that state on messages from the other join, which makes the ordering guarantees an important matter, and it is often addressed by using a unique identifier for a particular version of the joined record.

In order to provide fault-tolerance to stream processing, we might want to break the stream into small blocks, and treat each block as a batch (batch size is typically around a second). Also, atomic commits might be necessary to avoid causing side effects twice, and luckily, the overhead of transaction protocols can be amortized by processing several messages within a single transaction.

An alternative for transactions is idempotence writes, which are operations that can be performed multiple times and still has the effect as if it was performed once. Any operation can be made idempotent with some extra metadata.

Fault Tolerance

The batch processing approach to fault tolerance exposes *exactly-once semantics*, where it appears as though every record was processed exactly once.

In stream processing, waiting until a task is finished before making its output visible is not an option, because a stream is infinite.

Microbatching and checkpointing

- Microbatching breaks the stream into small blocks and treats each block like a miniature batch process.

- With microbatching, small batches incur greater scheduling and coordination overhead, while larger batches mean a longer delay before results of the stream processor become available.

- An alternative is to periodically generate rolling checkpoints of state and write them to durable storage.

- Once the output leaves the stream processor, the framework cannot discard the output of a failed batch. Restarting a failed task causes its external side-effects to happen twice, regardless of checkpointing or microbatching.